Every year in Australia 950 children aged 0-19 years are diagnosed with some form of cancer. In 2012, Ashleigh Bradford, now aged 21, was one of them.

Ashleigh suffered from severe headaches her whole life. At the age of 14, in June, Ashleigh began to lose her balance and was suffering from what she thought was “intense fatigue”.

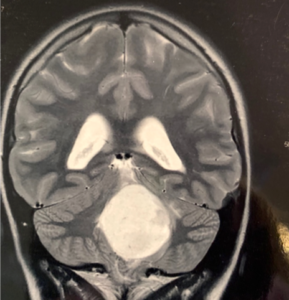

After realising her symptoms weren’t normal for a 14-year-old, Ashleigh went to Adelaide’s Women’s and Children’s Hospital. There she was diagnosed with a Pilocytic Astrocytoma of the cerebellum, otherwise known as a brain tumour.

Professor Peter-John Wormald, a leading sinus surgeon who invented tumour removal via the naval cavity, said symptoms of “headaches and fatigue are both very common for brain tumour patients”.

Ashleigh said her tumour was the size of a “golf ball”.

According to the Children’s Cancer Institute, 60 years ago nearly all child cancer diagnoses resulted in death. Today, 8 out of 10 paediatric patients survive. Leukaemia now has a survival rate among child cases of 90 per cent while childhood cancer has a survival rate of 50 per cent.

With more children surviving cancer, there has been a surge in the ‘late effects’ of cancer treatment. This includes both psychological and physical consequences.

Ashleigh described herself before her tumour as an “outgoing bubbly and optimistic person”. She was the head girl of her primary school, was involved in sport, was a high academic achiever and had a great group of friends.

After spending four months in hospital recovering from her surgery and beginning to relearn to walk, Ashleigh was faced with reality. She was going to be different from all her school peers.

“It was quite daunting,” she said. “I was embarrassed. I was still going to the hospital every day for occupational and physiotherapy and I was in a wheelchair at school for three months. I couldn’t relate to my friends anymore because I had matured in ways they couldn’t understand.”

Although fully recovered from her tumour, Ashleigh, along with 81per cent of paediatric cancer survivors, began to suffer from mental issues that stemmed from her cancer experience.

Years after her cancer, Ashleigh was diagnosed with anxiety.

Years after her cancer, Ashleigh was diagnosed with anxiety.

“It stems from my tumour experience,” she said. “I am no longer able to participate in the sports I used to love, and I now live a more limited active lifestyle. These are the things I used to associate with my identity which now fuels my anxiety.”

Jeff Darmanin, the acting CEO and director of Children’s Cancer Foundation, said cancer can be an impediment to a child’s belonging and can add a load of complexity in the teenage years to what is an already stressful period of life for many adolescents.

“This often can lead to mental health issues such as depression or anxiety,” Mr Darmanin said. “Cancer can be quite isolating. A child’s treatment can take up to five years.

“Often paediatric patients’ friends no longer want anything to do with the child because they are different. These patients can no longer play sport, are often in and out of school, are behind in academics and these factors contribute to their social isolation. It makes them difficult to connect with.”

According to Cancer Council NSW, 50 per cent of remission patients develop either anxiety or depression as a result of their experience and four out of five childhood cancer survivors will experience one or more mental health issue resulting from their experience.

“I feel like I missed out on the important social years of school where people start to form closer friendships and relationships,” Ashleigh said.

“I felt socially immature compared to my peers, but at the same time extremely emotionally mature.

“I was at odds with everyone in my year group in different ways and because of this it was hard to relate to them as much as it was hard for them to relate to me, the girl with the brain tumour.”

While Ashleigh’s tumour was removed in one surgery, on average 750 paediatric cancer diagnoses per year result in radio therapy treatment.

Professor Wormald said: “The very fact that they’ve received radiotherapy puts the child at further risk of other cancers. It is not just the management of the acute event; it becomes a lifetime journey.”

There are many events each year that raise money for cancer research including Sydney’s 7 Bridges Walk, Daffodil Day and Dry July. Mr Darmanin said 80 per cent of Children’s Cancer Foundation’s donations go to funding cancer research and “even a simple school sausage sizzle can help make a difference”.