Abandoned, disappointed, and vulnerable – that’s how many Australians in India feel after hearing the news about the travel ban and penalties the government has put in place for anyone who breaches it.

The controversial ban, described as racist, has affected more than 9000 Australians that are currently stuck in India, of whom 650 are classified as vulnerable.

The Indian Australian community and human rights advocates have raised concerns about this decision, but Prime Minister Scott Morrison has said this step was taken to prevent a third wave of coronavirus in Australia.

There’s no doubt Australia’s decision to close international and domestic borders had a huge impact on people’s lives. It separated families, lovers, friends. It left thousands of Australians stranded overseas and foreigners living in Australia unable to visit their families back home.

Australia’s international border is likely to remain closed until 2022, especially to high-risk countries including Europe and India. Interstate borders have reopened, however, the recent outbreak in Western Australia and three-day lockdown in Perth show how uncertain the situation is.

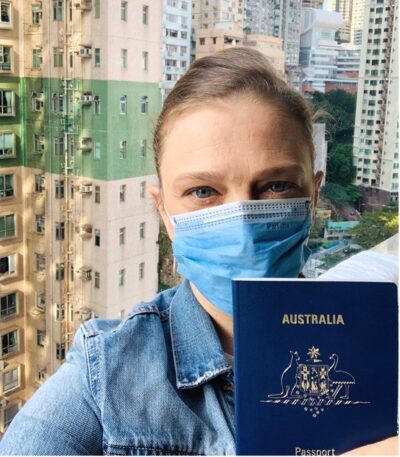

Living with uncertainty was everyday reality for Tara Tubman, an Australian citizen who lost her job in HSBC bank in Hong Kong, where she lived for 9 years, before returning to Australia in November last year.

“I was made redundant in August 2020 and was unable to obtain a flight until November 29 with Air New Zealand.

“Obtaining a flight was very difficult due to the inbound caps. I had two Singapore Airlines flights cancelled. I was then advised to book a flight with Thai airlines, but they closed international flights and refused to provide a refund for at least six months, which set me back $2000.

“I was required to give two months’ notice to cancel my lease so if I had got bumped off the Air New Zealand flight, I’d had been effectively homeless.”

As thousands of other Australian citizens overseas, she feels she was being unfairly penalised for her decision to live and work overseas.

“I didn’t ask for special treatment,” Ms Tubman said. “I was ready to undergo mandatory quarantine and pay for it. I wasn’t irresponsible, I wasn’t a tourist in the back of Peru who ignored warnings DFAT provided.”

Facing job loss, political instability in Hong Kong and limited opportunities to find a new role due to rising unemployment, she felt frightened and helpless.

Tara was unable to come home until November, after being made redundant in August last year.

She completed her 14-day quarantine in the Sheraton at Broadway in Sydney in early December. Except for visiting the emergency on her first day in quarantine because of a broken ankle, she landed in trouble with police for writing “help me” on the window of her room. Calls to the mental health line and doing artwork helped her to get through quarantine but on leaving the hotel she had to carry 90 kg of luggage despite her broken ankle because hotel staff saw her as a health risk, although NSW Health cleared her after three negative tests.

The situation was no better for Benjamin Pisani, an Australian citizen who was stranded in Greece. In May 2020, he secured an exemption from the Australian government to fly there as he owns a seasonal restaurant on one of the islands. After closing his business in September, he was unable to return home until December.

“I closed my business earlier than expected due to coronavirus and lack of tourism. The restaurant was my main income for a short time frame, and I was living off the last of my superannuation money, while desperately trying to get back to my family in Australia.”

After numerous e-mails to the Australian embassy in Greece, he felt the government had abandoned him. Finally, he managed to fly home on a government-sponsored repatriation flight due to qualifying for the financial hardship loan.

“I agree with border closures, but Australian citizens shouldn’t be shut out. I didn’t come to Greece for holidays; I went there to try salvage and operate my business. I ended up with no job and no income and I couldn’t receive any benefits as I’m not a Greek citizen.”

There are concerns border closures pose a threat to national identity. Australians stuck overseas have been blamed by their compatriots based on the belief that they have had enough time to come home. The feeling of national togetherness has been affected and it has created tensions between the states.

Even when Queensland opened its border to Greater Sydney earlier this year, Madeleine Rapisardi said some of her friends and family saw her as potentially infectious, coming from a declared hotspot. In December 2019, she decided to take a big step and move to Sydney from Brisbane after securing a job.

The move has been difficult for Madeleine, being away from home for the first time in her life and not having many friends in Sydney, added to the stigma the border closures have created.

“I try to keep myself busy most of the time to forget about it, but when I see my friends on social media hanging out all together or family events I’m missing out, it really hits me.

“The hardest part was missing my younger brother’s graduation. I could have watched the livestream, but it’s just not the same.

“I had to do a virtual funeral after my aunt passed away in September. I couldn’t attend it in person due to border restrictions and that made me sad. It’s hard, you know.”

Livestreaming and virtual events have become the norm due to coronavirus restrictions. After all, we spend more time online than ever. Some think virtual events are the future, but for now they simply can’t beat in-person.

Technology helps Gail Amoto, a temporary visa holder, to keep in touch with her family in the Philippines. It’s been more than two years since she last saw them.

“I was looking forward to going home and seeing my mum who turned 60. But then the Australian government decided to close the borders, so my plans fell through,” she said.

“I’m such a family person so I’m very homesick. The worst thing is having no option to go home because if I leave the country, I won’t be able to come back. I will lose my job and everything else I worked so hard for.

“Being far away from my family for so long and not having many friends here triggered depression and anxiety.”

Social isolation can have negative consequences on our psychical and mental health. It can interrupt sleep cycle, make us more prone to illness and cause long-term mental health problems.

Ms Amoto tried the free Medicare-covered mental health plan that provides 10 sessions with a psychologist, but she’s been waiting to get an appointment for months.

The Australian government has been criticised for not providing enough support to its citizens and foreigners living in Australia during the pandemic.

Experts warned coronavirus pandemic plan for mental health is not enough, while Centrelink financial assistance has been criticised for being too low to cover basic needs.

“I know the government has provided financial assistance for people who have lost their jobs or reduced work hours, but I think better mental health support is necessary, especially for young adults who struggle the most with the pandemic,” Ms Rapisardi said.

Border closures have impacted everyone, but opinions on the policy are divided.

“I think it was a good solution at the start of the pandemic when we didn’t know what we were dealing with,” Ms Rapisardi said. “But the longer this goes, it has more negative effects. It’s great we were able to control coronavirus by closing borders, but you’ve got to think about separated families and people who rely on tourism as a main source of income.

“Interstate border closures are affecting a lot of industries. While people’s health is the priority, the economy must go forward. Australian numbers are low so the government should be working on adjusting the economy to this new normal.”

How long will this new normal last? Will it become part of our “new normal”? The future is unpredictable.

Many are still waiting for the day when they will hug their loved ones, or when they will finally come home after months of being abroad. Dealing with uncertainty is not easy, especially when it feels as if it’s never-ending.