How the i-Maps Parra project re-frames city mapping to reflect Parramatta’s shifting, multilayered landscapes.

Several points on the hand-drawn map are marked with an ‘x’. Beside each is a description or a name. ‘Hair Salon,’ ‘Afghan Groceries’ and ‘Riverside playground’ look like they might all be within a few blocks of where I stand on Parramatta’s busy Victoria Road. I head toward the closest, ‘Afghan Groceries.’ I’m surprised by how intuitive it feels to follow this map despite my lack of familiarity with the city.

Just where the ‘x’ indicates it should be, there is an unassuming storefront with a sign reading ‘Star Grocery and Mixed Business.’ Inside, the store is busy with movement and colour. A man behind the counter is in lively conversation with a customer. One wall is lined with trays of nuts, spices and grains, and there are pyramid shaped stacks of pastel-coloured sweets in a glass cabinet.

The map I used to find my way here is one of a series of interactive, digitally accessible maps created as part of the i-Maps Parra project facilitated by Information and Cultural Exchange (ICE) – a community-based arts organisation working with emerging and under-represented Western Sydney communities. In 2017-2018, the i-Maps Parra project worked with a group of recently settled migrant women and their children in creating a suite of multilingual, multimedia maps of Parramatta.

The maps– grouped together under the name ‘ParraMa’– bring together audio recordings, drawings, videos, photographs, poems, songs and artworks relating to the women and children’s lives in Parramatta. They are collages of experience teeming with colour, life, humour, and practical advice: where to get fresh fruit and vegetables, the names of streets with nice light, where to find great parks, lists of ingredients for recipes.

Eager to learn more about the ideas and processes behind the creation of these maps, I have come to Parramatta today to meet with Yamane Fayed, producer of the Multicultural Women’s Hub at ICE. Fayed was the coordinator of the i-Maps Parra project, working alongside creative producer Alissar Chidiac and three artist facilitators: Eddie Abd, Jagath Dheerasekara and Jerome Pearce. I still have an hour until our meeting, so I busy myself looking at the patterned tins, boxes and packaged goods on the grocery store shelves.

Fayed meets me in the foyer of ICE, which is just a few blocks down the road from the grocery store. The foyer is a brightly lit space with a black and yellow mural of plants, flowers and a birds-eye view representation of a river system covering two entire walls. I ask Fayed about the mural when we meet, and she says it is a commissioned artwork titled “Burramatta Badu” by artist Shay Tobin from Boorooberongal clan of the Dharug Nation. The artwork’s bold lines and shapes map the Parramatta River across Dharug country from the east where the river meets salt water, toward the west and into the Blue Mountains.

I feel immediately comfortable with Fayed – she is warm and energetic and laughs easily. We walk through an open plan space to a room with folded tables and chairs stacked against the walls and Fayed tells me this is where the weekly i-Maps Parra workshops took place.

At Home in Parramatta

Recent increases in migration have contributed to Parramatta becoming one of the most diverse local government areas in Australia. The city has a long history of waves of migration including post-war immigration programs, refugee and humanitarian resettlement programs, and more recent temporary and skilled migrant programs. The most recent 2016 census indicates that the percentage of households where a language other than English is spoken in Parramatta is 68.8%.

Fayed says that the i-Maps Parra project envisioned a process of city mapping that would reflect and celebrate the city’s diversity. “I wanted the women to put their own map on Parramatta… and let them, with their language, create a Parramatta that’s theirs,” she says.

Early inspiration for the project emerged out of Fayed’s realisation that the women she worked with in Parramatta weren’t using street names or iconic buildings to navigate and speak about their city, but the personal and habitual landmarks of every-day life.

“For them, the colonial landmarks such as the bridge, or certain buildings- they’re not important for them,” Fayed explains. “What’s important is their local grocer who stocks turmeric. That’s a landmark. For them, Centrelink is a landmark…the playground is a landmark.”

A few days after meeting with Fayed, I meet with Abd, one of the three artists who facilitated storytelling and arts workshops throughout the i-Maps Parra project. For Abd, arts-based projects like i-Maps Parra provide powerful spaces where people can build and nurture connection. “That’s why community arts organisations are so important. It’s not just about the end product…you’re building communities,” she says.

Abd says that projects like those facilitated by I.C.E often provide the first point of entry into the community for recently arrived migrants. Because of this, they play a significant role in tackling isolation and dislocation.

Every Thursday for 12 months, the i-Maps Parra project ran in two parts. The first half of each session operated as a regular playgroup with storybooks, craft and morning tea. After the playgroup, one of the project’s artist facilitators would lead a creative activity, working in collaboration with the mothers and children.

The playgroup was what initially attracted many of the mothers to come to the i-Maps Parra program. “They came for the playgroup then realised ‘this is a different playgroup.’” Fayed says. “The mums kept telling others, ‘It’s not just for the kids, it’s for us too!’ For once, it was about the mums as well.”

The activities facilitated by Abd and the other artists varied in focus each week. Whether the group was working on drawing, collages, videos, audio recording or storytelling, the activities were delivered with a commitment to openness and flexibility. “You do your planning, and that’s key,” Abd says. “You have to really prepare… but then, during the workshop, you have to be so flexible. And adapt and read the room. And be open to people’s suggestions.”

The diverse media produced by the women and children in the workshops was collated and organised by Abd into the eight digital maps now available online. In putting the maps together, Abd says she was constantly checking in with the women, showing them progress, taking on suggestions and discussing and unpacking ideas.

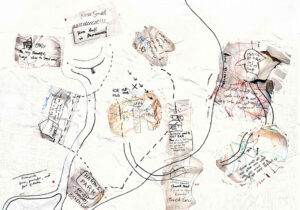

Each of the maps engages with a different theme: ‘At Home in Parramatta’ is made up of a collection of cut out maps, collages and multi-lingual text about what the women see and hear around their homes. ‘ParraMa Dreams’ features drawings of night scenes and lullabies sung by the mothers and children in several different languages. ‘In One Day’ includes videos, hand drawn maps and audio recordings identifying the shops, spaces and parks the women habitually visit.

These multilingual, interactive maps now exist as a guide for new migrants settling in Parramatta. “We had in mind, if someone new comes to Parramatta, what would they like to find? How could you find stuff if you’re a new migrant?” Fayed says.

Browsing through the online maps a few days later, I think about what I might identify as my own personal landmarks around my home in Dulwich Hill. The bookshop on Marrickville Road comes to mind. The stretch of red bottle brush trees on my walk to the bus stop. The hill near the Cooks River that catches the afternoon sun. The shortcut to the Skate Park where I take my nephew. I think about how long it takes to build familiarity with a place. Even when moving to a new suburb like I did recently it takes time, let alone moving to a new country. What a generous welcome it would have been to be guided to spaces like the ones I now know and love when I first moved to the area.

Shifting Landscapes

The next time I visit Parramatta, it’s to meet with Chidiac, the Creative Producer of the i-Maps Parra Project. On Chidiac’s suggestion, we meet at the Riverside Park. It’s a place that features in many of the women’s maps of Parramatta, and as I sit on a park bench before our meeting, I can see why. The Park slopes right down to the river, and there’s a children’s playground built into the hillside. It’s one of those great playgrounds that looks like it was created without an overconcern for safety– metal slides, rope ladders and climbing walls sit amongst shrubs and small trees.

Chidiac meets me where I am sitting at the foot of the playground. She has copper-red hair that sits in lively curls around her face, and there’s a light-heartedness in her manner that makes me feel at ease. In search of a place in the sun, we cross over the river via a low footbridge to a picnic table.

Looking back across the river, Chidiac tells me the playground where we met is relatively new. Up until a few years ago, this space was just a green slope, and kids used to slide down it on pieces of cardboard. “This is so firmly a part of the landscape now, this park. Kids gather here all the time,” she says.

“Even in this small stretch, over 10-15 years” Chidiac says, gesturing broadly to the river and the park, “there’s transformation.”

As Chidiac talks about the shifts in landscape that have occurred in this small area alone, the concept of a desire line comes to my mind. Desire lines are the informal tracks that are created, not through urban planning, but through numbers of people walking or moving where they wish for a path to exist. Nature writer Robert MacFarlane describes desire lines as the “paths and tracks made over time by the wishes and feet of walkers.” Well before the infrastructure of the riverside playground existed, kids were already gathering on the slope to play.

I am reminded of something Fayed told me about her work with the i-Maps Parra project. Talking with the women about their daily movements and walking with them around their favourite places, Fayed realised that the women and children were not just navigating Parramatta, they were changing the landscape in their interactions with the city, layering their own landmarks on top of colonial ones.

The maps created through i-Maps Parra reflect this constant shifting and changing of the city landscape. As flows of people navigate the city, certain spaces gain new significance, new landmarks emerge, and old ones find new meaning.

When we spend enough time in a place and see the landscape change, Chidiac says we develop a “memory map” of those spaces. Like her own memories of sites along this river and people’s shifting interactions with this space over time, she says that with the construction of new roads, diversions, walkways, and buildings we maintain a memory of what was there before.

Chidiac says that as a part of a family of settler-migrants, her own family’s relationship to and memory of the area only stretches back a few generations.

“We could not conceive what it means to Dharug people in terms of…thousands and thousands of years of those generational relationships to the land,” she says.

Reading about Dharug history in the area after my meeting with Chidiac, I learn that just west of the Riverside Playground, the area now known as Parramatta Park is a significant Dharug heritage site, containing ancient shell-middens and scarred trees where bark was removed to make canoes and water carriers.

The important, everyday landmarks the women identify in the ParraMa maps – the Afghan grocery store, the riverside playground, favourite parks, salons, fabric stores and restaurants – exist alongside these sites that mark tens of thousands of years of Dharug people’s deep and ongoing connection to this area’s land and river.

The more time I spend exploring the ParraMa maps, the more I think about these layers of history that exist in and around the landmarks represented. While the maps don’t aim to canvas a history of Parramatta, they do encourage a thoughtfulness about the way that experiences, memories and personal and community histories are embedded in the city’s spaces and structures.

Landmarks of Memory and Experience

From our position at the picnic table by the river, Chidiac points out another site that is within our vision. It’s a block surrounded by tall, wire-mesh fences, and Chidiac tells me it’s the construction site for the new Powerhouse Museum. The site has been the subject of major controversy recently because of proposed plans to dismantle and relocate the historic Willow Grove House to make way for the museum.

As Chidiac describes this site and the widespread community opposition to its removal (including a green ban), it becomes clear how many layers of experience and memory exist in this single landmark.

The Victorian house and its’ gardens are historically significant for Dharug and non-Indigenous communities in Parramatta. In the late 18th and early 19th Century, the site was one of the few riverside properties where Dharug people were permitted access to their own country and river. Later, Willow Grove became a maternity hospital and unlike many hospitals, it did not exclude single mothers or First Nations women.

In a submission to NSW Parliament in October 2020, the Dharug Strategic Management Group wrote that “the Willow Grove Site…is simultaneously woven into Dharug, colonial and the current urban cultural landscape.”

Chidiac says sites like Willow Grove are important spaces through which we can think and talk about complex histories. “If there’s a site that’s problematic, you don’t erase it,” she says, shaking her head in frustration. “You maintain it being problematic.”

In bringing to life some of the multitude of lived experiences and memories that are embedded in the city’s landmarks and spaces, I think the ParraMa maps offer opportunities for similar kinds of reflection.

When I return home after my meeting with Chidiac, I bring up the map titled ‘Parks’ on my computer. It’s bright and joyous, with drawings, collages, pop-up videos of kids playing, and audio recordings of women speaking about the parks they love. On this same map, cut out sections of modern cartographic maps are overlaid with the new lines, shapes and symbols drawn by the women and children.

I recognise the park that appears in the photographs and videos as the same one where Chidiac and I met earlier. The photos of the park are now a few years old, but in some of them, I can also see the block across the river where the Willow Grove House – at this point when I am writing – still stands.

You can begin to see the layers upon layers of interacting and shifting histories that exist in and around just this one riverside landmark.