Locked down with nowhere to go, Australians have increasingly turned their attention to family history research. What are the reasons behind the phenomenon and what impact has it had on local museums and historical societies?

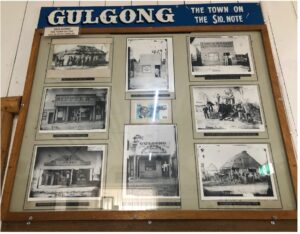

It’s a Saturday afternoon in June and a steady stream of visitors are walking around the Gulgong Pioneers Museum. Among the labyrinth of hallways and hidden rooms, you can find almost anything here, from pianolas, tractors and 1900s school magazines to ceramic toothbrush holders and the original $10 note.

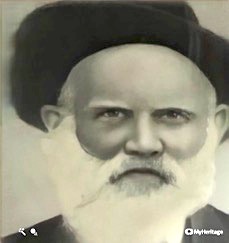

I am only interested in one item: a portrait.

I have travelled to Gulgong, a historic gold mining town 300km north-west of Sydney, for the weekend. Founded in 1870 after the discovery of gold brought 20,000 people to the area, its streets still look like something out of a 19th century period drama. As you walk down the town’s narrow Mayne Street, past the Prince of Wales Opera House – the oldest still-functioning opera house in the Southern Hemisphere – and the Ten Dollar Town Motel, it feels like you have been transported to a bygone era. A recipe for camel-stew hangs in a boarded-up shop window. The pavement is engraved with symbols that were once used to communicate road conditions to fellow travellers: “good road to follow”; “good haystack for sleeping”; “angry dogs”.

Fiona Griffin, a volunteer at the Pioneers Museum, leaves her post greeting visitors at the front desk to have a chat with me in an open-air section of the museum surrounded by an assortment of wheels and tractors. She has been working here for the past 18 months, just long enough to see visitor numbers more than triple since the start of the pandemic.

“I love Gulgong for the simple fact that it is built on its town history,” she says. “Since COVID, we’ve had no die-off. All of a sudden here we are all locked up and you start thinking ‘where are we going to go’?”

Fiona tells me the museum only remained closed for six weeks in 2020. The closure provided just enough time to clean the museum after droughts left its hallways full of dust.

Since its re-opening, she’s noticed a change in the museum’s visitors.

“They come in or ring up and say ‘well I know my grandmother came from there. Is there any information about the family name?’

“People are wanting to go and see where their family had been at different times; the areas they lived in, the sorts of jobs they had. It’s sparking an interest again as to what everyone’s heritage is.

“They want to know where their roots are, where they fit into the scheme of things.”

A Family History Boom

A boom in family history research has occurred over the last year with registry and state offices experiencing a surge in interest in genealogy records. In 2020, there was an increase of almost 40 per cent in purchases of family history records from Queensland’s Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, according to the Queensland Cabinet and Ministerial Directory. In Western Australia, the State Records Office experienced double the amount of traffic in 2020.

Online genealogy platforms also benefited. Over 200 million people, almost eight times the current population of Australia, visited the nonprofit genealogical website FamilySearch.org in 2020. That was an increase of almost 20 per cent from 2019. In the US, the genealogy site ancestry.com experienced a 37 per cent increase in new subscriptions from 2019 to 2020.

Fiona believes the family history boom has contributed to the significant increase in museum visitors over the last 18 months. She tells me this is partly due to the wealth of information available at the museum.

“We have those resources here where a lot of country places don’t,” she says.“I can tell you from the front desk where ancestors are buried and if they’re buried in nearby graveyards. I’ve got books with really old listings of farms and properties. We have a research centre here too. They’ve got miles of information.”

Online Materials Make Family History More Accessible

Back in Sydney, I meet with Ruth Graham the next day to learn more about the current boom. Ruth is CEO of the Society of Australian Genealogists. Established in 1932, the society is Australia’s oldest and largest. It is a community of family historians, professional genealogists and amateur hobbyists who she says are “enthralled with trying to find out both our origins and the origins of others”. The society runs regular events, lectures and formal courses on research methodologies and serves as a bridge between the community, government institutions such as the State Archives and big corporates like ancestry.com.

As I open the door to the heritage-listed Richmond Villa, the Society’s Head Office in Sydney’s Kent Street, Ruth’s cheerful face appears at the entryway. Leading me inside, past statues styled like ancient Greek sculptures, she asks if I recognise the space. I shake my head.

Ruth tells me that an episode of SBS’s genealogical documentary series Who Do You Think You Are? was recently filmed here in the main parlour.

“The one with Malcolm Turnbull.”

It’s hard not to gawk.

Upstairs in a seminar room with a view of Barangaroo, we discuss how the society has fared over the past year.

“We have never had as many people engaged with our events as we have since they’ve all been online,” says Ruth. “I can give you a really good example. We had an online conference just this past Saturday with 172 people. That would compare a few years ago to maybe 50 to 80 who might come in person.

“We found that people who were hesitant to travel because of their health or were in lockdown, we suddenly heard from them more. Around 50 per cent of our new members were coming from outside Sydney.”

Such an increase is not uncommon. This past February, the RootsTech Connect Online Conference, an online family-history conference run by a company in Utah, USA attracted over one million participants worldwide. In previous years, the same conference attracted between 30,000 and 100,000 people.

I can understand the attraction. While visiting my paternal grandfather in Canada in 2019, I came across a list of relatives, many with question marks next to their names and blank spaces in place of birthdates. A few hours of internet sleuthing ensued. After discovering that I could access old church records, census records and birth certificates online, I compiled a family tree of my paternal Scottish ancestors during lockdown – tailors, weavers and stonebreakers. I tell Ruth I now intend to investigate my maternal ancestors.

“I should give you a membership form,” she laughs.

While Ruth believes COVID has played a role in the increased interest in family history, she suggests several factors may be at play. These include the rise of genealogical television shows in Australia such as Who Do You Think You Are and Every Family Has a Secret, the rollout of the NBN across Australia making historical records more accessible and the public’s increasing familiarity with online platforms and digital content delivery.

Prior to the pandemic, 70 per cent to 80 per cent of the society’s events were held face-to-face in Sydney. With COVID, the society was forced to “flip all events online”.

“People can spend days on YouTube looking at cat videos but you can also watch lectures. I think family history has kind of fallen into that bucket,” says Ruth. “Everyone’s realised it’s easy to use these platforms. Content delivery can be a lot more informal and more accessible to a global audience. The old method of delivering lectures and education is gone. Everyone just needs a webcam.”

Dr Kate Bagnall agrees.

As a senior lecturer in Humanities and coordinator of the Diploma of Family History at the University of Tasmania, she’s seen a shift occur in recent years as more historical records and workshops became accessible online.

“There’s been a steady increase in interest in family history, probably since the 1970s. In the last 20 years, the growing availability of materials online has kind of democratised family history in a way that didn’t happen before,” she tells me over Zoom.

“If we’re thinking about UK research, previously you would have had to write away to the general records office, get your bank check in pound sterling, send that off and then wait. Now you log onto a website and its pretty instantaneous. You can get a certain part of the way pretty easily.”

Dr Bagnall says this accessibility has created a new type of family historian.

“The kind of die-hard family historians are still the same sort of people they were before but perhaps there’s a new kind of middle layer of family historians who are doing it more as a kind of hobby.”

Roots Tourism and Our Connection to Private Heritage

Rosemary Phillis, Secretary of the Riverstone and District Historical Society, has been volunteering there since the early 1980s.

While dealing with “two to three times” the usual number of inquiries this past year, Rosemary has also helped people start major research projects she believes would never have been tackled without the influence of COVID.

In a video call, she tells me that these projects, many of which are ongoing, drew visitors to the museum when it reopened in February 2020.

“Now that people can get out and about, some of them are coming because they want to see the museum. It’s been part of the ongoing journey for these people,” she says. “They come to Riverstone saying, ‘my ancestor was here in 1900. What would they have seen?’ “Well, they would have gone to school in the building that the museum is in. It’s trying to help them build the picture saying, ‘well look, you can walk out and look at this’.”

Dr Bagnall has a name for this phenomenon: “roots tourism”.

“People love going and finding where ‘their’ people lived. A lot of it is about a sense of identity, about where they’ve come from and how they fit into the world today.”

Private heritage has become more popular than all other forms of heritage in Australia, resonating with people of different genders, ages and educational backgrounds according to a University of Western Sydney study in 2020. Public heritage, such as historic monuments and state memorials, lack the same appeal with “very few, if any” participants visiting such monuments in the year prior to the study.

“It’s kind of sticky-beaking into other people’s lives. We find out lots of really intimate and personal information about people, sometimes good, sometimes bad, sometimes scandalous. When you research your own family, it seems more significant to you,” says Dr Bagnall. “It has a really strong emotional pull that a ruin or another building might not have.”

Towards the end of our conversation at the Gulgong Pioneers Museum, I ask Fiona to explain why people have become so drawn to family history over the last year.

She paused for a second before answering. “Everything’s become so unpredictable. Everything that we knew was okay has all of a sudden been thrown out the window, to the point where you can’t even be in your home with other family members.

“People are reassessing what’s important. Family’s becoming important because there’s a chance of losing that. I guess if you can’t be a part of that family unit, you can belong by researching more of it.”

Before leaving, there was something I needed to find. Hanging above the doorway among a collection of thousands of framed images, I found it.

Before leaving, there was something I needed to find. Hanging above the doorway among a collection of thousands of framed images, I found it.

A portrait. John Peck, 1885, Gulgong, A Gold Prospector. My great, great grandfather.

In a pandemic-ridden world, it seems that new connections can be found in unexpected places.