Drive My Car: A masterful portrait of artist in grief

Against a teal-tinted sky, a silhouette arises languidly, as if awaking from a deep slumber. No features are discernible on their shadowed face as they begin to weave a mysterious tale from the remnants of dreams – this is how Japanese auteur Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s 2021 arthouse drama, Drive My Car, begins. The film may start with a classic “once upon a time” opening but during its three-hour runtime, it’ll eschew the clichéd Hollywood trappings of overtly happy or sad endings. In Drive My Car, light melancholy and bittersweetness remain supreme, true to reality’s moral greyness.

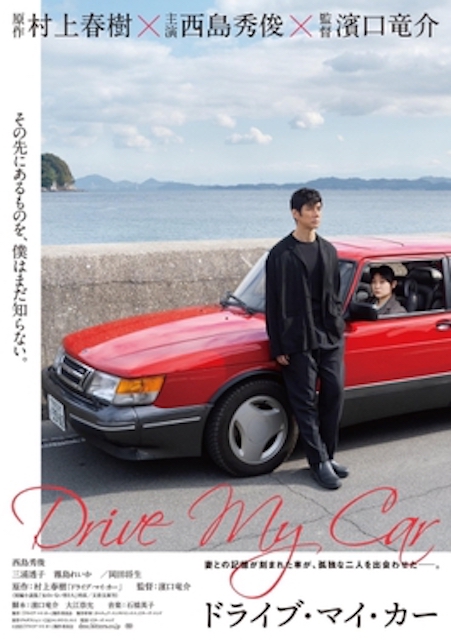

Adapted from acclaimed Japanese author Haruki Murakami’s homonymous short story, Hamaguchi’s masterful vision allows him to erect a delicate, humanist portrait of grief and regret. Now available to stream online for Australian audiences, the film follows theatre director and actor, Yūsuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishijima), as he processes the death of his unfaithful wife while putting together an original production of Anton Chekhov’s play, Uncle Vanya. With its gargantuan runtime and arthouse status, is Drive My Car worth watching for non-cineaste audiences? My answer is a resounding yes: despite the inaccessibility associated with highbrow art, Drive My Car retains an essential sense of warmth in its universally resonant themes.

From film festival darling to Oscar winner, Hamaguchi has made his mark on international cinema through releases such as Happy Hour and Palme d’Or competitor, Asako I & II. Drive My Car’s success has cemented Hamaguchi’s status as one of Japan’s most promising filmmakers: he is the third Japanese director to be nominated for an Oscar and Drive My Car is the first Japanese film to compete in the prestigious Best Picture category.

Drive My Car’s acclaim also represents a victory for slow, subversive cinema in its home country. Far from the reign of cinematic masters of the past, such as Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu, the dominance of idol-culture in Japan’s current entertainment landscape has led to a devaluing of arthouse productions. These productions subsequently suffer from a lack of funding compared to mass entertainment, with unskilfully produced franchise films and comic book adaptations reigning at the box office.

In myriad ways, Drive My Car can be seen as an untraditional ghost story, where rewound cassette tapes of a past lover’s voice haunt the living, rather than incorporeal forms. In a forty-minute prologue, viewers are treated to the domestic bliss of Yūsuke and his wife, Oto – only for this illusion to shatter with emerging evidence of Oto’s infidelity. Yūsuke, unable to confront his cheating wife and afraid of damaging their current relationship, is left alone when Oto suddenly dies. How do we reckon with our grief and rage, when it’s directed at someone we cannot forget but is gone forever? Drive My Car keenly observes that life itself is a constant ghost story, where the legacies of the dead burden the living, inevitably entangling the present with the past.

In myriad ways, Drive My Car can be seen as an untraditional ghost story, where rewound cassette tapes of a past lover’s voice haunt the living, rather than incorporeal forms. In a forty-minute prologue, viewers are treated to the domestic bliss of Yūsuke and his wife, Oto – only for this illusion to shatter with emerging evidence of Oto’s infidelity. Yūsuke, unable to confront his cheating wife and afraid of damaging their current relationship, is left alone when Oto suddenly dies. How do we reckon with our grief and rage, when it’s directed at someone we cannot forget but is gone forever? Drive My Car keenly observes that life itself is a constant ghost story, where the legacies of the dead burden the living, inevitably entangling the present with the past.

Being a linear story, Drive My Car may be told without flashbacks, but not for a second does Hamaguchi, and in turn we, as the audience, forget the indelible shape regret has taken in Yûsuke’s life. Finding himself unable to act, Yûsuke turns to directing. He accepts a residency in Hiroshima and is assigned a driver, the taciturn Misaki Watari (Tōko Miura). Hamaguchi, deeply committed to portraying life in its truest form, is concerned with how the individual threads of our lives entwine with others. Short-lived but life-changing connections are central to his films, with the unlikely pair of Yûsuke and Misaki gradually finding solace in one another through their shared pain, leading to a heart-wrenching denouement.

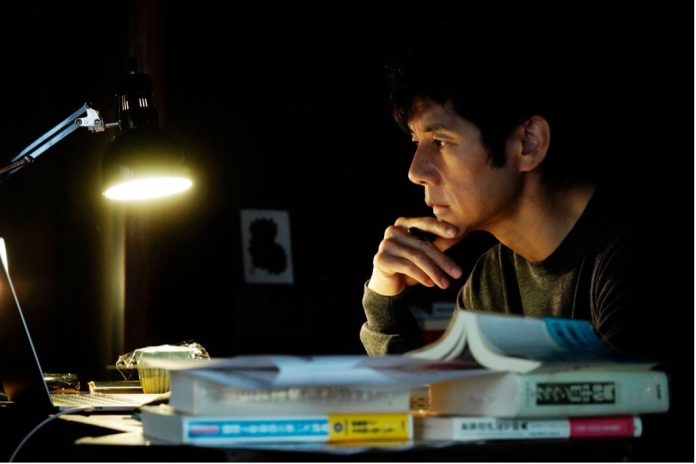

The deceptive simplicity of Drive My Car masks a grander narrative in the subtext: the role of artistry in our lives. In Hamaguchi’s films, the masks worn are often more revealing than someone’s ‘true’ face. Performance is a conduit for actor Yûsuke to grapple with his loss, where the immortal words of Uncle Vanya and their fierce emotional intensity allow for him to come to personal conclusions amid daily life’s inherent miscommunication and banalities. Here, Nishijima demonstrates his remarkable acting range: the emotional high and lows of the film wouldn’t be as believable without his flitting between Yûsuke’s reticent persona and melodramatic anguish in his performance as Vanya. However, some theatre scenes don’t land as well as others; the repetitive practice scenes detract from the film’s more fascinating, central relationships and stronger performers.

Despite the lack of flashy shots, Hidetoshi Shinomiya’s cinematography is frequently astonishing. Still shots operate in complete harmony with the film’s abundant silences, capturing Yûsuke’s stasis. Cathartic moments appear all the more electric, with a memorable shot being when Yûsuke and Misaki smoke together, their cigarettes brightly lit against the night sky. It’s an understated mid-shot, but one that perfectly echoes the quiet connection forged between the two characters in a film rife with misunderstandings.

An instant classic, Drive My Car is a gorgeously introspective, cinematic triumph that does more than justify its lengthy runtime. Hamaguchi’s magnum opus earns him a permanent place in cinema history’s halls of fame.