Why the key to Australia’s on-screen diversity lies behind the writers room

With Crazy Rich Asians, Fresh off the Boat and The Farewell, the tides for Asian representation in the US are finally turning, and fast. Yet on our own home turf, aspiring actors and writers are questioning why Australia’s television industry is falling behind.

Actor Rizcel Gagawanan, who was raised in an Australian Filipino household, said that during her first audition for a major television role it became apparent that racial discrimination in the industry was still prevalent. “I wanted to turn down the audition the moment I read the script. The Filipino characters were stereotyped as maids and gold diggers – it was appalling to read,” she said.

Yet after her agent’s advice, Ms Gagawanan auditioned for the part. “I know many of my fellow actors have even been asked by them [casting directors] to put on an ‘Asian accent’ which is extremely uncomfortable. This is the sort of pickle that many Asian Australian actors find themselves in. We want to stand up for what we believe in but at the same time we need to earn a living.”

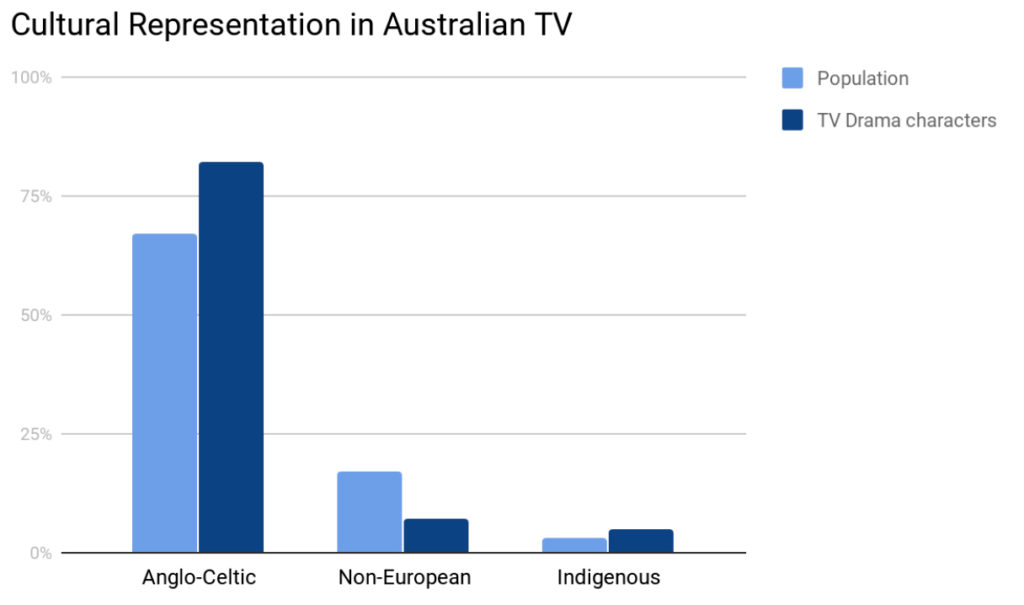

Unfortunately, television roles open to Asian Australian actors are scarce. According to Screen Australia’s Seeing Ourselves Report (2016), Australians from a non-European heritage accounted for 17 per cent of the population, yet less than 10 per cent of Australian TV characters represented this cultural demographic.

Earlier this year, The Bachelor sparked a wave of criticism from viewers for its portrayal of Kristen Czyszek. Despite coming from a European background, Kristen’s appreciation for Chinese culture, along with her fluency in Mandarin, led to her being tagged as the show’s “China Girl”. The show featured the sound of a gong, along with ‘Chinese music’ each time she appeared on screen. Many were quick to point out that this was problematic, considering that only two contestants from an Asian background have appeared on the show over the course of its seven seasons.

One twitter user wrote, “You know what would be better than Kristen who loves China? An actual Chinese bachelorette on #TheBachelorAU.”

Casting director Graeme de Vallance said: “It’s a sad thing to say but the reality is that the majority of applications we receive come from Caucasian individuals.” Since its establishment, Mr de Vallance’s A Cast of Thousands has been the casting company for Australia’s major tv shows. On the question of The Bachelor’s lack of diversity he said: “There is never a requirement from producers to skew our casting choices. It’s never based on cultural background.”

Screenwriter Mina Kang said the issue doesn’t start at the audition but within the writer’s room. Ms Kang worked as a director and writer for Jubilee Media in LA earlier this year. “Working over there made me realise the power writers have to create roles that can showcase under-represented voices. Then when writers are given the added duties as showrunner, they can help executives decide how and who is going to bring the story they ideated to life,” she said.

In US television productions, the ‘writer/showrunner’ model is used in which the writer is in control of the creative direction of the show, script distribution and casting. The current system in Australia still finds the executive producer responsible for these decisions, meaning the writer is often excluded from final casting choices.

Ms Kang explained: “TV shows like The Family Law are proving that a great writer, who can both capture the authentic experience of Asian Australians and normalise diversity, is key to great television. We need to give them greater creative control.”

Along with many screenwriters, Mr de Vallance also hopes to see the production system change. “As a casting director, I’m usually kept at arm’s-length. So, I would definitely appreciate being more closely involved with writers because it really is a puzzle when casting individuals, and the right individuals, to tell the story you want,” he said.

Many Australian organisations, like Screen Australia, have recognised the need to empower screenwriters from minority backgrounds. In August it launched the ‘Digital Originals’ with SBS, a program aimed at developing content by under-represented screenwriters, including culturally and linguistically diverse individuals.

Rizcel (right) one of the lead actors in Secret filmed in October. (Source: Kevin Shin)Rizcel Gagawanan worked as an actor for Mina Kang’s original screenplay, Secret. This was her first time working with a director/writer who was Asian Australian. “I could finally relate to a character; her race wasn’t used as a ‘marketing tool’ – she was multifaceted and comedic, and her cultural background was just an incidental part of it,” she said.

“Of course, it’s tempting to just fly to the States, but I know opportunities for more Asian Australian actors will grow if we first embrace and empower our diverse writers. I want to be part of that process.”

Ms Gagawanan will be running this year as the first Asian Australian committee member for the Women in Theatre and Screen Organisation where she hopes to develop opportunities for talented female writers from minority backgrounds in Australia.