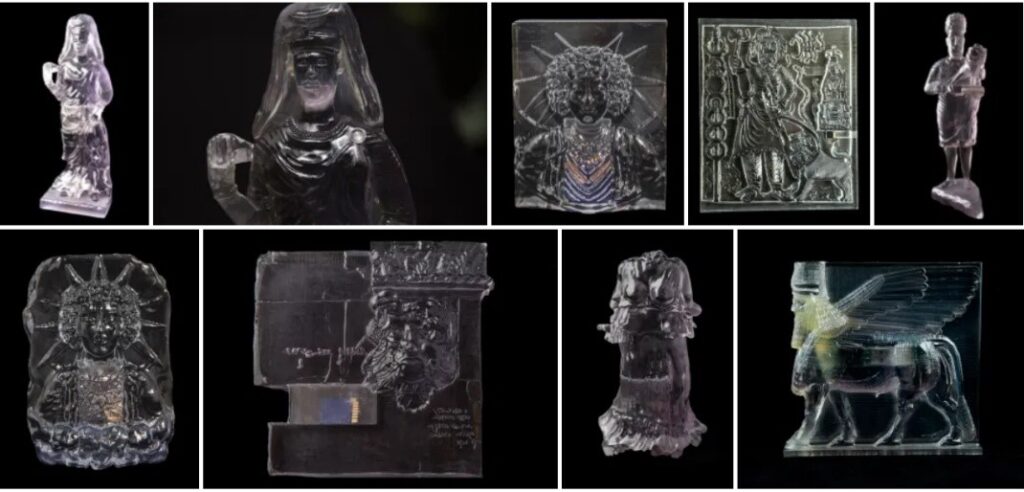

ISIL pillaged Hatra in 2015, releasing viral YouTube videos that showed militants with sledgehammers gashing and decimating statues belonging to other Muslim sects (fig.1). In response, Iranian-Kurdish new media artist-activist, Morehshin Allahyari, created an artistic project named Material Speculation: ISIS (2015-2016). Using 3D printing technologies, Allahyari and her team replicated 12 Hatra and Assyrian cultural sculptures and disseminated them virtually and materially through zip files and objects (fig.2). These reproductions sustain the iconicity of cultural artefacts that go against ISIL’s religious ideology. As such, they are forms of resistance and nodes of activism which have the potential to preserve culture for future spectators. Indeed, by sharing her (re)productions via zip files and objects, she opens up an artistic-activist space whereby people can collectively partake in archival practices against ISIL’s destruction.

Although the reproductions maintain a likeness to the original, they lack its aesthetic and feel because of the machinic characteristics of 3D printing technologies. Not only has the reproduction lost the touch of a hand, its subtle cracks, its colour, but it has also lost what Benjamin calls its aura. In other words, through its mechanical reproduction it no longer holds a unique space and time in history (Benjamin, 1968).

But this loss of aura is transmuted into a new ghostly, aesthetic object. Allahyari’s statues are not so much substitutions that reconstruct a loss of cultural heritage but rather they spotlight the sculptures as affective ghostly (re)productions that radiate a tangible loss for the spectator. In the ISIL videos, each crashing chop on the stone artefacts results in a thunderous echo which wounds the netizen with a material and symbolic experience of heritage destruction. Allahyari’s petite sculptures still attend to this loss but she presents it in a contemplative setting, rather than in a spectacle of violence. The translucent reproduction seems to glow and shimmer because of the light’s effect on the divine quasi-glass-like material. Allayari’s creation seems to bleed and melt into the background, and its glossy form is hazy. The statue’s glowing and serene aesthetic allows me to pensively reflect on cultural heritage loss on terms that are not determined by ISIL, but by my fellow people, and me.

This work that I made (fig. 4) demonstrates how the hypermediacy of various traditional and new media technologies can remediate, entangle, and become absorbed by each other to improve the immediacy of a certain representations. (Bolter & Grusin, 1999). There is a push and pull between hypermediacy and immediacy, depending on the viewer’s reading.

Indeed, Allahyari encourages and inspires us to partake in recreating, editing, and disseminating such artefacts for ourselves and others by sharing files that contain archival information, images, and 3D model files. Since 2016, Allahyari’s project is still exhibited on a website named Rhizome, a word that is an appropriate figure for the dissemination of Allahyari’s files on the internet. For Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, rhizomes are non-hierarchal and complex multiplicities of entanglements and connections (Deleuze, Guattari, 1980). Anyone with access to the internet, regardless of their social standing, can connect and entangle with others, forming complex and interactive political formations that have the potential to grow. Indeed, each of Allahyari’s files are nodes that have the fiery potential to ignite new collaborative creations. With each download and edit of Allayhari’s files, the audience plays a role in expanding the archival collective – something that is vital to grassroots activism and resistance.

These artefact reproduction files have democratic and political function in bringing objects and information to the masses (Benjamin, 1968). This reconfiguration of art is thus grounded in a socio-political foundation, whereby potentially emancipatory knowledge can be scattered, shimmered, and felt throughout public spheres or internet archives. Having control of this public archive is inherently political, as Jacques Derrida explains, because shaping knowledge, perception and memory is an exercise of power (Derrida, 1995). There is a political and digital war of aesthetics between ISIL’s destructive propaganda videos and Allahyari’s counter-archive (Rancière, 2010). Whereas ISIL disseminates distressing artefact destruction videos to wound spectators and to empower themselves, Allahyari makes these artefacts perceivable in a new light and within an internet-archival context. In doing so, she reclaims control of the memory of the statues and reinstates them with her own aesthetics. People who partake in Allahyari’s artistic-activism project thus resist cultural heritage destruction by redirecting it into a pensive and collaborative archive that is built on our own terms, and from our own visions.

In protest against ISIL’s attempt to self-fashion a controlled propaganda, Allahyari sows a multiplicity of digital seeds for collective and artistic activism. By disseminating files on the internet, she triggers the political potential for more netizens to join in and edit them. Although these potential (re)productions may differ in their aura, appropriations and modulations, they are united by the common grounds of pensively bearing witness to cultural heritage loss. The strength of this rhizomatic space is in its participatory value whereby artistic-archival practices are determined, not by ISIL, but by a shimmering motley of people, and the potential of people yet to come.