In 1996, John Perry Barlow declared the future of cyberspace would be independent of government and corporate control. Utopian and idealistic, it reflected the general optimism about the liberal and egalitarian promises the Internet would bring to society.

Nearly 25 years later, digital technologies and the Internet are deeply interwoven into every aspect of our daily lives; from how we communicate, to work, to how we spend our leisure time, and how we consume goods and services.

Yet, Barlow’s optimistic and somewhat naïve perspective has been dismantled.

We have seen how the Internet has reproduced the very social and political structures it was trying to evade. Ownership and control has consolidated in the hands of a select few, namely Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google (FAANG), creating a “corporate monopoly” in which capitalism has been refashioned . Discussions around issues such as data capitalism, surveillance, the blurring of the public-private, and the proliferation of misinformation in the form of fake news are only increasing with intensity.

The digital art project Conflict In My Outlook aims to examine these very power dynamics we see embedded into such networked technologies. Curated by Anna Briers, the UQ Art Museum exhibition will be split into two parts over 2020-2022, which will be hosted both online and offline respectively.

This review will solely focus on part one—Conflict In My Outlook_We Met Online—which was released as an online exhibition on August 21, 2020. Arguably, there has never been a more fitting time for its release, where in the midst of a pandemic we have found ourselves increasingly reliant on digital technology. Here I will be discussing the aesthetics and experience of the overall exhibition itself, and arguing how it effectively illuminates the ‘dystopian reality’ that the Internet has engendered, by means of subverting the very digital architecture of the network itself.

The title of the project, Conflict In My Outlook, was taken from an error message from Microsoft Office, which essentially signifies a glitch or failure to connect to the network. As Briers articulates in her Exhibition Essay, the title was chosen to reflect back the ‘cognitive dissonance’ currently underpinning our relationships to new, networked technologies.

The exhibition features 12 Australian and international artists who have created various post-Internet artworks, provocations, and essays with future plans to feature talks, podcasts and interviews. These all aim to address the overarching questions: how does the Internet mediate and shape social relations and ideas? And what will become of privacy and democracy in context of the new economic logic of data capitalism?

These questions are not easy to answer, let alone ask. Nonetheless, the project attempts to address the multiple layers of these provocations with artworks that use a mix of user-generated content scraped from social media, geo-location technologies, interactive engagement, virtual and augmented reality filters, and data visualisation techniques.

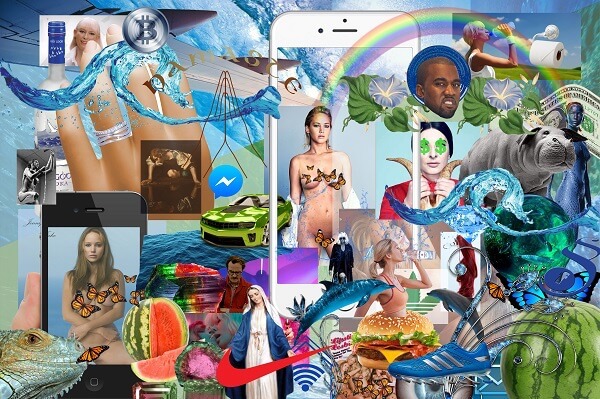

The result is a very post-internet aesthetic, a “native product of modern network culture” that’s rhizomatic in nature, open-sourced, with an almost DIY amateurish feel. The online exhibition is an example of digital mediation, layered onto the public domain of the Internet while simultaneously being privately consumed from the comfort of your own home, asking us to ‘rethink the materiality’ of the public sphere. This blurring of boundaries, between the digital and physical, creates a hybrid space that is mapped through the duality of the software and hardware itself.

With artworks employing satirical images of political leaders such as Trump, cat memes, emojis, and BuzzFeed-style personality quizzes, it feels precarious and in a way completely ‘useless’. But it’s this very ‘uselessness’ that draws attention to the medium itself, not the content. It very much echoes Marshall McLuhan’s prophetic claim that “the medium is the message”. This continuous reminder of the medium can be framed within the context of ‘hypermediacy’, where the combination of images, sounds, text and video construct “multiple representations within a heterogeneous space”. In this way it remediates other traditionally artistic forms into new digitally aesthetic ways.

The aesthetics of the project, both its property and experience, reflect the historical present context of ‘Network Formalism’: the way power formations of communication technology exists to favour corporate and marketing interests.

Since content is now produced with the intent focus of being highly visible and circulated, aesthetic qualities have shifted to shareable, often ‘meme-like’. In a way, the artworks included in Conflict In My Outlook are ‘living’ spaces, by encouraging audience interaction, exchange, and collaboration.

For example, featured artist Xanthe Dobbie ‘s piece Wallpaper Queen has audiences answer a personality quiz that generates a digital collage of their ‘Queen’ identity. With no one set outcome or ‘finished’ product, it showcases this shift in the flexibility that is inherent to new media art, being constantly remixed and reinterpreted to offer different perspectives.

It is also interesting to consider the exhibition’s use of affect in the audience experience. This relates to the way that art can affect the viewer’s nervous system and create a physical sensation and response in the body. Conflict In My Outlook illuminates the potential to experience the transference of affect from the digital to the offline world.

A prime example is Kate Geck’s rlx: tech digital spa, where audiences are able to participate in ‘meditative experiences’ and ‘psychic cleansing’ entirely online. Designed to combat social media anxiety and network fatigue, it ironically uses the architecture of the network itself (the source of the anxiety) to subvert neo-liberal notions of productive labour.

The participatory nature of the artwork, like art movements of the past such as Dada and Fluxus from the 20th century, enables social dialogue on how our own digital practices are tangibly affecting our offline lives.

While all art can be considered ‘technological’, “always tied to a technology of production and technology of mediation”, what makes this exhibition unique is that digital technologies are employed in every aspect of its production, circulation, and reception.

With the exception of since passed artist Kenneth Macqueen’s watercolour cloud paintings (which have been reinterpreted to refer to cloud-computing), all other artworks are distinctly digital, using digital tools and software to produce the final piece.

It has then been circulated and received by audiences entirely online, by means of their website and Instagram. As audiences navigate the exhibition, their attention is likely fractured between scrolling through other apps or switching back and forth between tabs on their browser. So, the exhibition is integrated into the experience of the Internet itself, a reflection of the attention economy and its implications on current digital practices.

Each artwork in the exhibition is reflective of Brier’s strong ‘positionality’ on networked technologies. Despite having a light-hearted feel to the artworks which tend to be easily digestible, it contrasts against an explicitly dystopian message—the decay of democracy and fragmentation of society as a result of our increasing reliance on networked technologies.

For example, featured art collective Chicks On Speed combine cat memes and drone warfare mashed up in a karaoke music video, to point towards the use of the same pattern recognition technologies in such contrasted applications. The use of satire cleverly imbues a strong political message about networked technologies through humour and by means of the technology itself.

Another example is Zach Blas’s artwork titled Utopian Plagiarism. In a screen capture recording, he downloads famous political texts as PDFs ranging from Manifesto Contrasexual (2000) by Paul B. Preciado and The End of Capitalism (As We Know It) (1996) by Katherine Gibson and Julie Graham. With the catchy riff Get Off The Internet by Riot Grrl band Le Tigre playing over the top, he substitutes all mentions of ‘capitalism’ and ‘economy’ in the downloaded texts and replaces them with ‘internet and ‘network’. In effect, he highlights the current capitalist logic underlying networked technologies, encouraging us to think critically of network hegemony.

Conflict In My Outlook_We Met Online harks back to early Internet aesthetics and culture, before it took a capitalistic turn and began to exploit and mine our personal data. The Internet is not inherently doomed, nor should we give up on its potential power to mobilise people to connect and collaborate across virtual time and space. In this aesthetic reminder of the utopian possibilities the Internet could provide, Conflict In My Outlook effectively articulates where we went wrong and where we must make changes as a society.

While we may find ourselves currently trapped in a dystopian reality, it is important to remember how new these networked technologies are—a lot of the world’s population can recall life before its existence. Inevitably, with the evolution of any new technology, we must grapple and navigate the tensions that arise, and in doing so, re-imagine a future where these technologies are used for good.