Jakarta tethered to unsustainable water sources

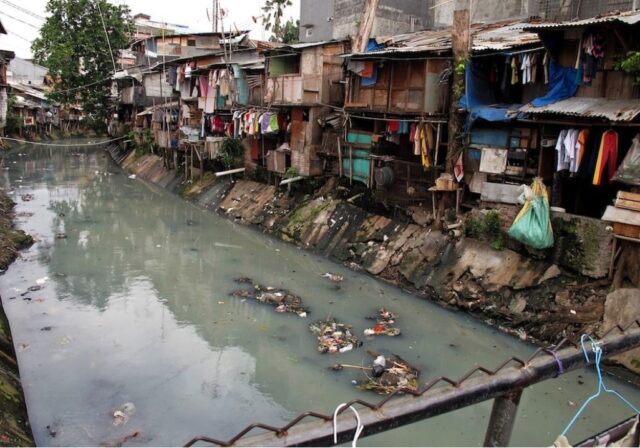

A dark gloomy afternoon presides over the banks of Jakarta’s 13 rivers, its extensive bay, and the minds of its more than ten million inhabitants. The ocean gradually seeps closer inland, bursting through the wooden shacks that rest on fragile stilts. These lively homes line up one-by-one forming local urban villages, known as kampungs.

Fishermen stand along the coastline eager to catch their day’s supply of produce that will be traded at old fish markets. Jatinegara, Muara Baru, Doyan Ikan and Sentosa are some of the most popular spots. The smell of freshly cooked catfish lingers in the air, carried by the salty ocean breeze.

As the day ends, fishermen reel their small wooden boats back into the bay, young children run freely in the narrow alleyways that line their homes and families gather for supper by the sea.

Jakarta Bay (Teluk Jakarta) is a low-lying and swampy coastline, 514km, stretching along the North of Jakarta City on the Indonesian island of Java. Each year for the past decade, climate change has caused the sea to rise by 0.5cm. Kampung residents have lost loved ones, been forced to flee their homes, leave behind belongings, and find new sources of income away from the sea.

Source: SOMO research.

Jakarta is at a critical point. Over the past decade, the Indonesian Government has implemented the Master Plan for the National Capital Integrated Coastal Development programme (NCICD), a multi-billion infrastructure project to counteract the threat of sea level rise and flooding. Thousands of fishermen, women and their young children who have inhabited the bay for generations are being evicted from their villages, with no clear migration or relocation plan.

These kampung residents have been denied their right to the sea.

Andi Dwipasatya is an Australian resident, originally born in Bogor city, south of Jakarta. She lived in Jakarta for over 30 years, and explained that life was difficult. “Life is not fair for us. If you live in the middle class and below, in poverty. We struggle for life itself. But it’s okay. We’re used to it.”

The Colonial Era

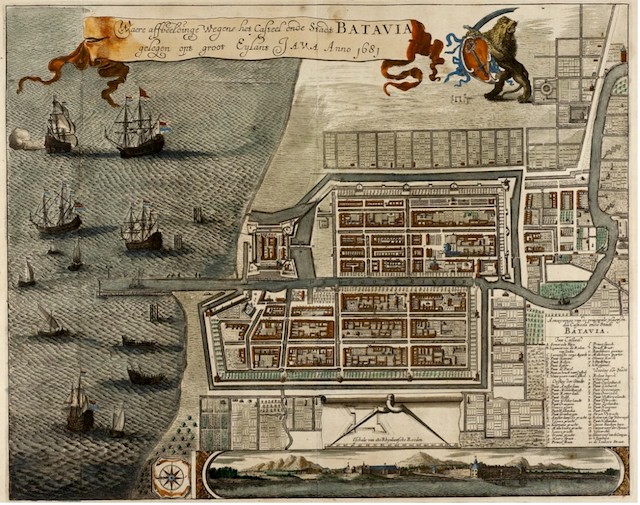

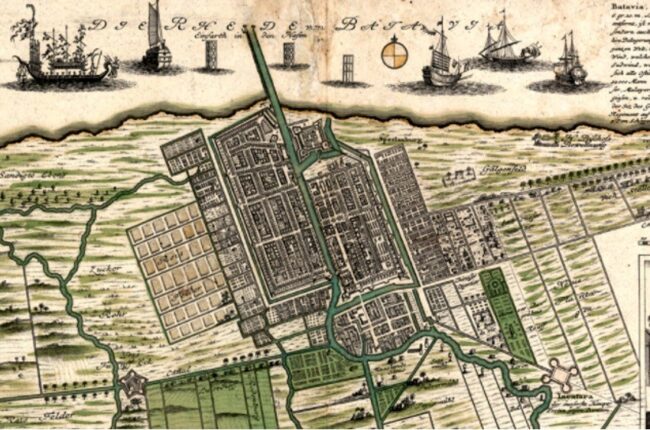

The geography of Jakarta is well-connected to rivers, has direct access to the sea, and rains 300 days of the year. A city consumed by water. This made it a desirable spot for settlers and export traders in the colonial era. In the early 1600s, the Dutch colony sailed onto the shores of Indonesia and rapidly developed the land. Roads and port facilities were laid over vegetation and soil beds that once absorbed the rain. This meant the Dutch needed to find a way to capture this excess water to reduce flooding in the city.

The ‘canal’ brought from the Netherlands was thought to be the solution. “The Dutch built the canals, because in the Netherlands they have their own canal system where they use boats to transport people and goods within the city,” said Altaf Muhammad Haekal Dikri, a Jakartan resident completing his undergraduate degree at the University of Sydney.

The canals were not only constructed for trade activity and flood mitigation. This infrastructure racially divided Jakarta (formerly known as Batavia) into two urban centres: the West and the East. By the mid 1700s, many of these canals began to deteriorate. Over time, earthquakes caused sediment to build up in the canal system, stagnating the flow of water. Deadly bacteria began to propagate. This quickly turned into an epidemic of typhus and malaria, particularly in kampungs where there was inadequate sanitation to limit the spread of disease. As the urban poor became increasingly sick, the Dutch elite moved South of Batavia to escape the chaos.

By the 1870s, the Dutch had built iron pipes underground to deliver potable water to European settlements. However, the locals were left in informal dwellings forced to retrieve water from disease-infested canals.

This colonial legacy means that to this day fewer than 50 per cent of Jakartans have access to piped water.

A World Resources Institute study published in 2019 shows that the more intermittent the water service, the more likely it will be contaminated. This is because stagnant water is at higher risk of spreading waterborne illness and microbial infections. Gaetano Romano, Senior Program Manager at Engineers Without Borders, has worked for the past 20 years with rural populations to solve water scarcity. He said that when water is not available at all, there is an impact on sanitation and hygiene.

“Overall, there is a negative impact on health. Diseases that are related to water have an enormous impact on communities, and malaria is one of them. Diarrhoea is another.”

It took many decades for the government to build pipes throughout Jakarta’s poorer areas. Only a few were supplied, one kampung at a time, forcing families to live without clean and regular water. Native residents relied on street vendors to access water when there were pipe leakages or shortages. This was a costly, limited, and an unreliable source.

Dikri said, “Water is not cheap. Whether you want to be on the grid or not, some people simply can’t afford it. They share with the people in their informal housing.”

Post-Independence:

After independence in 1945, the population skyrocketed. In 1880, the population of Batavia was just under 100,000. By 1950, it was over 1.5 million and by 1995 it exponentially rose to just shy of 9 million.

Many multinational companies set up offices in the city centre. This brought new jobs, investment opportunities, cultural activities, and foreigners, many of whom decided to stay. Willem Vervoort, Professor of Environmental Science and expert in hydrology systems at the University of Sydney, said that “if you have a big population centre, you have a big pressure on water resources. Migration to urban areas creates pressure on urban systems and drinking water”.

He explained the flip side of responding to increasing population demands. Once clean water is widely accessible in a city, it tends to lead to more migration. This means more infrastructure. More pipes need to be built. And more legal battles need to be fought over scarce water supply. “It’s a universal problem that has to do with social and economic development. How do we manage migration?” he asks.

Romano, from Engineers Without Borders, explained that controlling the flow of people from rural to urban areas is extremely difficult. Governments often have a reactive, rather than proactive response, meaning basic services tend to be in short supply. This was the case for Jakarta in the years following 1945.

Locals were forced to engineer new ways of accessing water at minimal cost. They discovered the answer in groundwater. Thousands of wells were built to access water from below the earth.

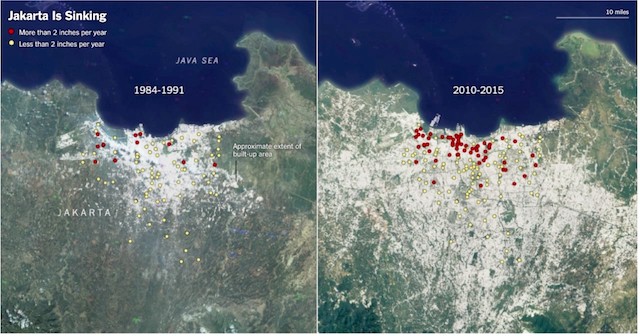

In the decades that followed, Jakarta began to sink.

Prof Vervoort said: “People started using groundwater because they have this perception that it is cleaner than surface water which is commonly used for wastage purposes.”

An over-extraction of groundwater stored in aquifers (underground layers of rock that hold water) drove this rapid sinking. Rocks are like soaked sponges, so the more water extracted, the more the soil compacts and collapses. Land subsistence, when the ground sinks, is the biggest contributor to flooding in Jakarta today.

Locals have adapted to gradual sea level rise – an ecological process that has shaped Jakarta for centuries – but the extremity of this threat is increased by the frightening reality of a sinking city. Over the past 300 years, unregulated extraction of groundwater has led to roughly a 7.5cm drop in soil height per year, with certain regions experiencing up to a 17cm drop. This means when sea level rise hits the shores of Jakarta, it flows hundreds of meters inland, flooding entire homes.

Since 1990, Jakarta has sunk 4 metres. Around 40 per cent of the city now lies below sea level and many experts believe the city could be completely underwater by 2040.

Recent World Health Organisation (WHO) research, published in collaboration with the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), found that more than 60 per cent of Jakarta’s urban population depend on groundwater while only 26 per cent have access to tap water.

Aquifers are naturally refilled by rain. However, Jakarta’s growth over the past century has meant large concrete structures, such as roads and buildings, have been laid over the natural environment. These impermeable surfaces cover the soil, meaning rain cannot be absorbed into the ground and aquifers cannot be restored.

More than 95 per cent of Jakarta’s surface soil and vegetation is suffocated by concrete and asphalt.

Dikri confirms this saying, “Flooding is one of the biggest issues in the city because it happens every year. The government tries to find ways to mitigate it but it’s a pretty hard thing to do since most of the city is made from concrete. There aren’t enough parks or open spaces.”

He explained that heavy rainfall picks up rubbish and toxic chemicals as it flows through the city’s streets. Eventually, it ends up in Jakarta’s rivers.

Andi Dwipasatya, a former local, explained that water distributed through Jakarta’s formal piped network was collected for many years from these polluted rivers. But there was not enough time to clean the mud from the water, and water providers “just put chlorine in it before distributing it all around Jakarta”.

“The water was not drinkable, unless I boiled it because the smell of chlorine was so bad,” she said. “We put the water in a jar for two or three days until the chlorine smell was down. We didn’t have a filter at that time.”

Her experience mirrors millions of households around Jakarta. She said her family and neighbours in the 1980s dug wells, sometimes more than 10 metres underground, to extract clean water. It was cheaper than paying for the usage and maintenance of water the city’s privatised amenities network provided.

Dwipasatya soon became “fed up with Jakarta’s life”. She was “scared”, a fear many of her friends shared.

A sinking city muddied by a colonial legacy means sea level rise is an existential reality that threatens to wipe out entire kampungs.

Jakarta’s Future

In 1991, The United Nations declared water a basic human right. Today, water equality is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs) published in the UN’s 2030 agenda. However, Romano explains that the value of water as a good is understood in different ways. Each country, community, household, and individual values water differently.

The Indonesian government is rushing to private investors in the Netherlands to save the city from sinking. Since 2011, redevelopment plans have been deeply enmeshed in profit seeking agendas. Dikri said corruption is widespread and has led to tensions in the city over the past decade.

Jakarta Bay has turned into a battleground between the rich and poor. The sound of roaring protests echoes along the shore.

“There isn’t one way to tackle the issue, and Jakartans have to look at it from different perspectives,” he said. “When you choose one option, there is a drawback to this, an opportunity cost. Some people will be disadvantaged, and some will be advantaged.”

Romano agrees, saying there are no solutions that “work everywhere for everyone”. Those disadvantaged by one solution can be raised by another. But this can only be made possible if development plans work with the local environment and communities’ practises, values, and social beliefs.

The first land reclamation proposal for Jakarta Bay was drafted in 1995 by then President Suharto. In 2011, after more than a decade of legal battles, the Indonesian Supreme Court approved the allocation of development permits.

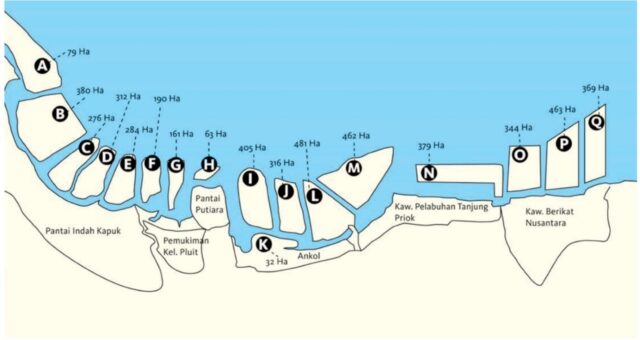

The National Capital Integrated Coastal Development program (NCICD) began in 2014 in collaboration with a syndicate of Dutch engineering and consultancy firms funded by the Dutch government. They plan to augment the existing sea wall along Jakarta Bay, construct a Western and Eastern outer sea wall, and 17 islands that would act as additional sea barriers.

“They’re building an artificial island in the north of Jakarta and stretching it all the way from Tangerang, which is like a satellite city West of Jakarta, to the eastern part of Jakarta. That’s one of their mitigation techniques to combat sinking, and sea level rise,” Dikri said.

City officials and Dutch investors have marketed the islands as luxurious condos with golf courses and yacht quays to wealthy expatriates and travellers from nearby nations. This more than US$40 billion infrastructure has attracted many Dutch and Indonesian real estate tycoons.

Source: SOMO research.

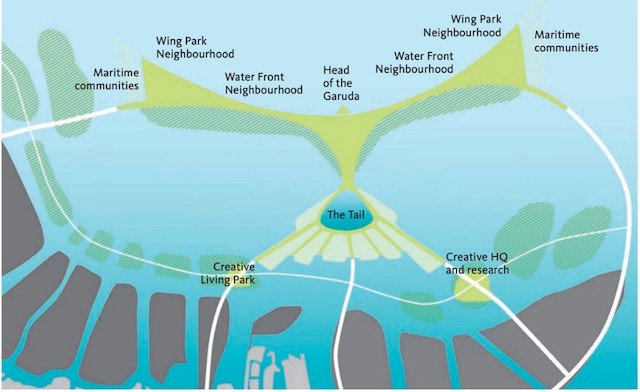

The shape created by the collection of islands is referred to as the Great Garuda, inspired by the national symbol, a giant mythological bird that takes centre stage on the national emblem, the Garuda Pancasila. It is believed to be the ‘protector’ of the people.

However, 13 permits have been annulled in the past six years. Many fishermen took the government and Dutch developers to court arguing this infrastructure would damage aquatic ecosystems. In 2014, they formed the ‘Save the Jakarta Bay Coalition’.

The Dutch consultant enterprise, DHI Water and Environment, was funded by the Indonesian Environment and Forestry Ministry in 2012 to investigate the potential for ecological damage. It was found that up to 586 hectares of fishing grounds would be destroyed, resulting in a loss of US$1.3 million in fishermen wages.

Indonesian Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fishery research in 2016 concluded that this initial figure was grossly underestimated. The true cost was closer to US$11.4 million. It found that fishermen would lose more than 75 per cent of their monthly income.

The government is also considering mass migration of its 30 million inhabitants in the greater metropolitan region to the island of Borneo; a desperate yet perhaps necessary attempt to save the city. Dikri explains: “2050 I think is the right time to relocate the capital city, because right now Jakarta is facing a lot of population growth. They need to save the city.”

Source: SOMO research.

Dwipasatya agrees this might be the best, if not only option left to save the city. She has been grappling with this reality for nearly 50 years. In 1973, when she was living in Depok, a suburb in Jakarta, she discussed this solution with friends and family. “I said ‘why don’t we move to South Sumatra to get a new capital?’”

A few years ago, the government established a small-scale relocation program. Housing, education, medical facilities, and other needs are subsidised if an individual or household is willing to pack up their life in Jakarta and move to South Sumatra, Lampung, Bengkulu, or another island close by. Dikri said, “It is an attractive option. My housemate is originally from Central Java but she chose to move to South Sumatra because the government provided her with housing and education for her children.”

But many don’t want to leave Jakarta. Memories, cultural sites, and battles fought to secure their homes are a part of their identity. “Jakartans still prefer to live on Java Island, because that’s where all their families are, and you can’t really replace that. Indonesian people are very conservative with their culture; they tend to stay where they feel a sense of belonging. If they move somewhere else, they’re going to feel like they’re foreign,” Dikri said.