It’s January 2021 and I’m being interviewed for an elective I want to take at uni: Service

Learning in Indigenous Communities (SLIC). I’m a little nervous about the service

component. Helping people is in my blood, but lately it’s been leaving me burnt out and

exhausted.

I tell the panel: “I’m a young Chinese Australian, passionate about Indigenous rights. I feel like it’s impossible to find my place in a country and culture that still under-privileges and even denies the existence of those who were here first. I’d like to find a role where I can do something without contributing to the problems of colonialism and White Saviour complexes. This unit feels like the best way to do that.”

A month later, I find myself at uni a week before semester begins, sitting at one of five round tables covered in colourful tablecloths and furnished with little baskets of textas and lollies, and some traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artefacts. We’re in the Physics Road Learning Hub, but I feel more like I’m in a Kindergarten classroom.

As students, we’ve been asked to attend a compulsory pre-placement workshop centred on an empowerment program called Family Wellbeing, or FWB. The adapted program is an unexpected take on cultural competency – a skill that has received growing attention in recent years.

Although FWB was designed by, and for, Aboriginal people, the issues the course addresses are ultimately universal themes that tap into the joys and suffering of what it means to be human. The delivery is unexpected too – lots of journalling and deep and meaningful discussion, prompted by handouts and PowerPoint slides.

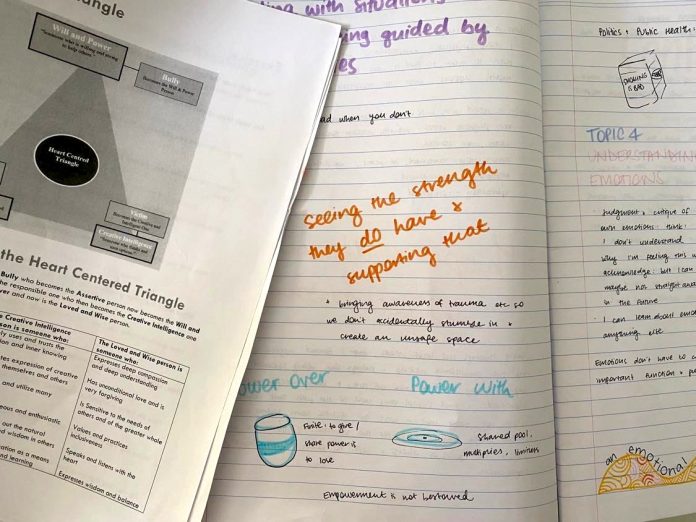

I’m particularly struck by a lesson called Understanding Relationships. Our facilitator pulls up a familiar looking “Drama relationship” triangle on the projector, featuring a bully, a rescuer and a victim. FWB models two more relationship triangles: the next one along is “Negotiating”, characterised by conflict resolution and win-win outcomes. The final one is “Heart Centred”, and this is where I really stop for a moment.

Within my family network, ‘rescuers’ run rife. I often feel burnt out and fatigued from the litany of instances where I’ve tried to fix or save people I care about. In line with the theory we’re learning, it’s become part of my identity – this idea of being needed. But what kind of person/friend/sister are you if your sense of self relies on the pain or suffering of others?

The learning doesn’t happen until I’m on Palm Island – an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community off the Queensland coast. It is home to over 3000 Manbarra and Bwgcolman people, the latter of which translates to “one tribe, many people”.

I’ve been there nine days, and tomorrow morning I’ll be on a small plane headed for Townsville. The sun is setting over the ocean – a glistening, jewel-coloured mass of water with light patches where the coral reefs grow. On the other side of a grassy esplanade stand seven other university students and an academic and her partner, who is from here. The sound of their laughter carries on the warm April breeze.

We’ve spent the week meeting people from the community and conducting informal interviews that assess the impact of a maritime training program recently run on the island. After discussing everything from land and sea culture to youth employment, it seems fit to host a Kup murri to bring everyone together for a meal before we leave.

It’s a celebratory feast like no other I’ve had before. An aunty sets up trestle tables and our small SLIC crew serve up potatoes and pork and cabbage that’s been cooking in a big hole in the ground all day. With thirty or forty people fed and the evening fast approaching, I wander a short way from the group and take out my camera.

It’s a warm balmy evening, and I snap a photo of a palm tree silhouetted against the setting sun. A local approaches and tells me to angle my lens a little more “that-a-way”. I snap again. It’s a better shot. We talk, about photography at first, and then how I’ve liked the island. I feel compelled to mention the emotions the trip has brought out in me, how being out on the sea, beneath blue skies, moved me to tears earlier in the week.

My companion gives me a thoughtful look. “You and me, we’re the same you know. You’re like us,” he says. I raise my brows in question. “See how we do the food, how we let the older people eat first. In your family you do that too.” It’s a slight leap – in my house, meals are more like a free-for-all. But we do take special care of the grandparents and the older aunties and uncles when they’re there.

“It’s the young ones I worry about,” he confesses. “They need to remember their families. Family is everything.” I nod in agreement. My family are everything to me. Delighted squeals ring out from the beach where a bunch of children are running along the sand. The man shoos me away, saying “Now that down there is a good photo! Go take it!” I take a couple and they end up being my favourites of the entire trip.

Prior to the FWB workshop, I never considered myself a culturally incompetent person – at least not within my own Chinese-Australian community. When it comes to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, I’m still learning; even writing this piece has been a challenging task, trying to speak of a community without speaking for it, watching what terms I use and how I use them.

There’s a lot more I could say about the complexity of taking learning from one culture and applying it to another. There are dangers in drawing parallels between cultures and homogenising diverse experiences for the sake of a few. These are all real problems that have led to all kinds of injustice. Yet there’s another significant perspective: acknowledging shared values and common qualities across cultures can remind us that in our deepest, heart-centred essence, we are all the same.

In the Heart-Centred triangle, the Rescuer becomes a “Loved and Wise Person” who listens and speaks from the heart. This dynamic moves beyond a willingness to listen and compromise to draw on qualities like wisdom and humility. Family and friends no longer need saving because they are not helpless and in danger.

As people of Chinese heritage, my community has suffered racist remarks. We are losing our language and our traditions. But we are far from helpless and within each of us is a strength I’m only just beginning to see, one so big and intricate that no amount of hate could tear it down.

Palm Island is filled with strength too. This is what FWB teaches: to see the strength in others and ourselves; to realise that as culturally different people, we don’t need to be helped. We just need to be heard, and in turn, to hear.