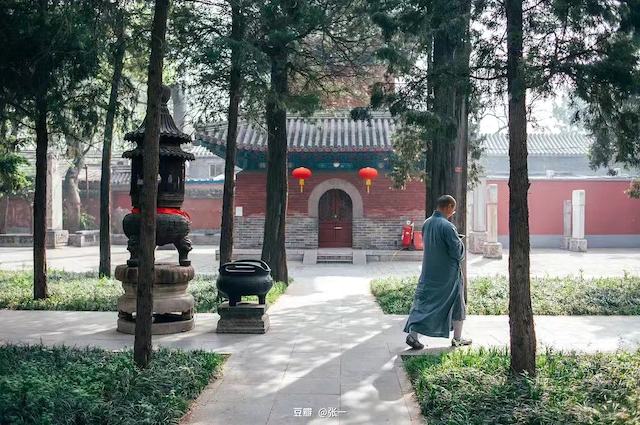

It is not so much for their age that the temples in Beijing’s hutongs make a claim upon people’s hearts. The value emanating from their beauty, peace, and tranquility wonderfully renews and changes a weary spirit.

Hutongs are alleyways in Beijing where local people live. These are not just residential places – they make Beijing stand out from other major cities worldwide since they symbolise the Chinese capital’s architecture and urban planning. Temples in hutongs are a crucial part of this architecture, and have been for a very long time.

Yet few people are aware of the role they once played in community life. The temples provided the public with space for participation in community activities, including healthcare, trading, working, and education. Zhao Zhan, a local resident, said, “I was raised in Dongcheng district around Douban hutong, and I lived there throughout my childhood until I moved to another place when I got a job.”

Zhan added that he visited the Lama Temple, which we often referred to as Yonghegong. “It was the closest temple to my home, so I often went there to pray for many things, including performing well in school, landing a good job, and wishing for a good partner.

“Visiting the temple for prayers does not mean that I am religious. I view temples as places where wishes have a higher chance of becoming true. Of course, I work hard to fulfil my desires. Besides prayers, I also visit the temple just to enjoy peace and tranquility.”

YongHegong is the largest Buddhist temple in Beijing. Its construction began in 1694 to serve as part of the city wall. Emperor YongZheng and his son, Emperor Qianlong, used it for different purposes. While Emperor YongZheng used it as a symbol of defence against enemies, his son used it to house hundreds of Tibetan students and monks in the 1740s. Since then, the site’s only function has been as a monastery and a temple.

Zhan said there are many other temples where he was raised but he only visited YongHegong. However, failure to visit the others did not mean they are not important. They have a rich history from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and only the people who understand their value pay attention to them.

Ju Su, a Beijing Normal University scholar, said Beijing alone had about 1500 temples between 1740 and 1950. During this period, one could see a temple within a radius of 150 meters from any point in the city. The temples were so concentrated as the city covered an area of about 40 square kilometres. Every hutong in the city had two to three temples separated by a maximum of 500 meters.

“Temples were used for many purposes at that time,” Ju said. “The people of Beijing saw them as a form of investment. House owners were required to maintain the houses even if they didn’t live in them; hence, temporarily renovating the houses and turning them into temples was a better option. Temples were maintained by the community, implying that owners were relieved of maintenance expenses.”

The temples were used for many functions. Besides prayers, people grew different types of plants in the temples. Ju spoke of a temple known for beautiful plants: the Fayuan temple in the Xicheng district was famous for its lilac blossoms. Dajue Temple in the western suburbs of Beijing was also known for flowers in the springtime. “Thousands of visitors go to Honglou Temple in the north of Huairou district every autumn to see the beautiful ginkgo trees,” Ju said.

The temples were also used as parks, to enjoy nature but also as amusement parks for holding annual fairs. Some of the temples were used as makeshift hotels for the city visitors, others provided space for libraries where people could read books.

Temples in hutongs were at the heart of residents’ lives, Ju said. Parents took their children to a temple for treatment when they fell ill, relying on the Chinese medicine skills of the monks, and since the temples housed many old-style private schools, children went to the temples for lessons when they reached school age. The temples also provided people with work options when they didn’t get a job in farming or business.

“Older people used to visit these places to spend their later years and get assistance as they grew older. Therefore, attendants needed to be available to care for them. Working in temples was considered a good occupation,” Ju said.

In the 1950s, temples were used as small public squares where residents met to discuss important community issues. They were homes to a surprising number of identity-defining and community-building activities, and the homeless and the elderly found accommodation in these venues.

Today, most temples in Beijing hutongs are no longer gathering spaces for residents. Even religious functions are not conducted in temples. “Many of the temples have been turned into small business stores where local residents buy goods,” Ju said.

The Beijing municipal government has now stepped in, introducing renovations to restore the atmosphere of the past. The government invited urban planning technicians, conservationists and other professionals to address the poor conditions of the temples, update them for a better environment and modern living, and preserve the ancient sites.

People using the temples were given a choice to leave or stay. New apartments were provided to those who chose to leave; those who stayed were provided with spaces to stay as the restorations began. The work has been funded with financial subsidies set aside for Beijing hutongs. The renovation works have already transformed one of the yards into a few one-bedroom apartments with modern facilities where families can live.

Hou Lei, a planner for the Tiantan sub-district in Beijing and a scholar at the Central Academy of Fine Arts’ School of Architecture, said 1,332 residents left hutongs for modern communities. “Living space used to be less than 25 square metres, but after the evictions, the per capita living space had increased to 110 square metres.” Hou said. Vacant space will be used for public meetings and for entertainment and cultural activities as the work continues.

Hou and his team are scheduled to begin repairs at the Qinghua Temple in Tiatan sub-district. Although the temple has been there since the Qing and Ming dynasties, the central and front halls are still in good condition. The tiles, carved railings and cornices are also well-preserved. But the yard needs attention. “We will begin the works from inside the temple to repair the untidy yard and transform it into spectacular scenery,” Hou said. “We will then move to the ancient architectural repairs.” Hou’s team aims to make the venue available to the public when the repairs are completed.

The renovations will aim to recapture the historical appearance of the ancient royal temples. Renovators will not add colours or repaint the faded beams to keep their aged look. The original wooden pieces will be carefully reused to regain the authentic look, and only wood that has rotted wood will be replaced for the decayed pillars.

“To maintain the integrity of the designs, the original materials and craftsmanship will be applied,” Hou said. “We will not use modern glue and cement. The nails used will also resemble the traditional which were made of bamboo.” Bricks and the tools used to cut and polish them will be handmade. “These principles will educate the current generation about the old ways concerning architecture in China,” Hou said.

Lin Fan, an engineer and a former resident, said he can’t wait to see the temples after the renovations are finished. “I’ve been raised around these temples and I recognise their value to the residents. Walking through the structures enabled us to connect with the experiences of the people who lived in ancient times. I want to experience the feeling again because of the pride it brings,” Lin said.

Liu Jirong, a local student majoring in art at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, feels proud of the transformation. She said the beauty of the temples inspires her studies. Her favourite temple in Beijing is the Fayuan Temple, which she loves because of its rich history and beauty. But the temple is now in poor condition and she’s waiting for the restorations so she can relive her childhood moments.

“I would like to contribute to the repairs, particularly in refining the arts. This will be a perfect opportunity for me to practice what I’ve been learning,” she said. “Chinese architecture is rich in art, so it provides learners like me with motivation to learn more and work harder.“

The temple is also popular for housing many celebrities. Renowned Chinese poet Xu Zhimo and his Indian counterpart Rabindranath Tagore used to visit Fayuan Temple together in 1924. This adds to its cultural significance. The temple is now home to the China Buddhist Literature and Heritage Museum and the Buddhist Academy of China, and will remain there after the renovations. There are also plans to open it to the public.

With the effort to improve the conditions of the statues, walls, columns, pillars, roof, and gardens, the temples can regain their former place as public spaces that can accommodate traditional exhibitions “just as the temples were traditionally used”.