It is around 7:15 am and I am in the back seat of my aunty’s car. The roads leaving Balmain are quiet in the new morning light. I am 8 years old and have just begun my first year at my new school. My understanding of the world only goes as far as what I have experienced myself, blurred by the lens of childhood naivety.

As we queue behind other early risers to cross the bridge into the city, I chat with my cousins on either side of me, who also attend my new school, about our personal current affairs; other kids, which teacher was ‘mean’ or how hard the homework was. I pause for a moment and peer out the window. Across the road is a complex. It has been split into four separate storefronts, each business with a different industrial speciality.

My eight-year-old eyes immediately focus on the ‘We Are Signs’ storefront, a business clearly dedicated to making signs. Below their large self-proclamation is a smaller sign. A rectangle, with a Disney princess on it.

I ask my Aunty about it while we wait in traffic. Apparently, the Prime Minister at the time, who I only vaguely know to be a woman, had lost her shoe at a protest the week before. Her name is Julia Gillard. And the protest was for Indigenous Rights on Australia Day.

It is this experience that I now view as my indoctrination into the world of news. The moment remains important to me, signifying the vitality of local voices in the circulation of news.

Since then, my interest in news and current affairs has only grown. As a Media and Communications Student at the University of Sydney, I am fortunate enough to be learning about the changing Australian media landscape in the 21st century, marked by digitisation and echo chambers.

While many Australians remain engaged in the news cycle, others are turning away and disconnecting. A 2022 Reuters study reports that interest in news has fallen from 64 per cent in 2017, to 51 per cent in 2022, with many actively avoiding the news.

Australia has a significantly concentrated media landscape with News Corp Australia and Entertainment Co., two separate media companies, together owning more than 80 per cent of the metropolitan and national markets. The top four media companies control 95 per cent of revenue among daily newspapers. This contributes to an ill-informed and disenfranchised public sphere that lacks proper platforms for discussion.

But every now and then, an independent voice resists. On that commute to school in 2012, I witnessed this for the first time through the satirical comment on Gillard’s mishap.

I now drive to university myself but often pause at the same set of traffic lights I did ten years ago. The amusing signs on the front of the business change monthly. In an age where news both generates and dissipates rapidly, the stability of the ‘We are Signs’ routine slows me down to actually dwell on the event.

One day, instead of driving past, I park my car. Walking through the garage door, the workshop is quiet. On the walls are smaller versions of the signs they have displayed throughout the years. It is a place of creation, with paint splashes on the floor and commissions half completed.

To my left is an office. I knock on the door gently. Steven Cattermole, the owner and founder of the business, spins in his swivel chair to face me.

We chat for a bit, and I tell him I am a fan. Steven tells me he gets that a lot, mostly from people who live close by. As I ask him if I can sit down with him one day this week, he takes a deep breath, hands on hips, and looks at the whiteboard calendar on the wall. It is busy.

“7 am? Thursday morning?”

The early morning wake-up is worth it.

On Thursday, I first check Twitter for the daily news. Simultaneously scrolling through celebrity updates and the latest in Ukraine, I am met with the familiar discomfort that is consuming media in the digital age.

I message Steven and ask if he wants a coffee for our morning meeting. He says no. He already has one from his favourite local café he goes to every morning. I am learning Steven likes both continuity and community.

Cattermole, 53, has been at ‘We Are Signs’ since 1993. Cattermole is the last full-time employee in the business he founded with friend Ross Williamson, who became part-time in 2019. After COVID, many of his employees moved to sub-contracting and freelancing. This morning it is just Steven and me in the workshop.

We discuss the signs, exchanging our respective favourites from across the years.

They started the billboards in 2009 to prevent graffiti. I ask him, 15 years since commencing, why he refreshes it monthly. Surely if it’s to prevent tagging there are other methods demanding less regular requirements of creativity.

“Let’s make them laugh,” he says with a smile, adding that it’s difficult when the news is so awful. “At the moment, I haven’t wanted to talk about the Ukraine War. There’s nothing funny about it.”

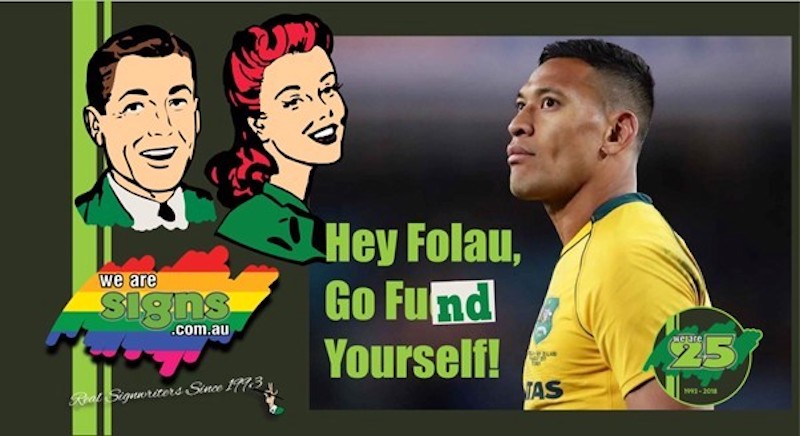

I ask him which sign he felt compelled to make. He mentions a 2019 story, where Rugby Australia and former player Israel Folau went to court over his dismissal. Cattermole’s sign proclaimed, ‘GO FUND YOURSELF!’. He is proud of the pun, but recalls that others in Balmain were not as pleased.

For this poster, a man rang him early one morning complaining.

“He said it was filthy… but I had some email banter with him, and he eventually came around to it. I think because I made a few points about it all.”

His sign had started a discussion. Away from the media conglomerates, Cattermole had contributed to the news cycle. A revolutionary act in a time when the dominance of media moguls can feel almost oppressive.

Toward the end of our conversation, Ross enters. He is helping Steven with some signage at a local hairdresser later in the day. I ask Ross, a contributor to the business for nearly 28 years, for his thoughts on the sign.

“We have to look at news from a different angle. Put an interesting perspective on some things,” he says, leaning against the door to the breakroom, arms folded. He is about the same age as Steven, and although no longer wearing matching uniforms, the two are obviously a pair with their banter and common goals.

Together, they energise local political discussion and have done so for the past decade. In a time when the national media landscape is fraught with change, Steven and Ross champion the voice of the public.

The essence of Cattermole’s business is tangible, resisting the rapid digitalisation of the 21st century. As marketing moves online, Cattermole emphasises the importance of a good storefront and in-person presentation.

As contemporary media companies obsess over the 24/7 cycle, continually rewriting, publishing and posting, Cattermole works on a different timeline. His signs are monthly, yet another resistance to modern media habits. His signs encourage a return to the true purpose of public debates.

Although his younger former employees may become freelance, Cattermole remains in his office, close to his local café and coffee. Working tirelessly, he reminds us to think in opposition to the agenda-setting media conglomerates.

While my days as a media and communications student prepare me for change and flexibility, my drive home past ‘We are Signs’ reminds me of the importance of keeping some things the same.