To the average Sydneysider, Leppington will only be recognisable as the terminating station on the T2 Southwest and Inner West Rail Link. Ask a politician and it’s the land of insatiable development, a delectable 15-minute drive from the new Badgery’s Creek airport. But as my father and I drive through a variety of fresh, asphalt highways and dirt tracks, windows down, pointing out settings to both our childhood memories, it’s clear that Leppington is losing its old colours.

Nonno Vic is on the back veranda tying the shoelaces of his worn sneakers when Dad and I pull up, at about 9.45 on a Saturday morning. He’s got his signature tweed flat cap on and a new navy polo shirt that my aunt must have bought him. The small talk between him and Dad is a lot shorter than usual; Nonno’s too excited. We will be visiting his best friend today, Ida Favretti, Leppington’s unofficial mayor.

My grandfather, Vittorio ‘Vic’ Poles, lives under a kilometre from the station, but for a predominantly old, pastoral suburb like Leppington, that’s just down the road. He’s a sprightly man of 83, fit and tanned, with a patchwork of sunspots covering his bald scalp from endless days of tending to his five acres of fruit orchards, vegetable patches and cows. He shuffles behind us to our car around the side of his brown brick house surrounded by flower beds of pinks and reds, the odd tomato plant, and piles of autumn leaves.

There’s an ensemble of trucks parked opposite Nonno’s house, and it’s a tight fit for me to jump out and close the front gate without Dad blocking the single-lane road. Nonno Vic points with a crooked finger to the shopping centre being constructed a minute from his place and laughs.

“I can’t even get out of the gate most mornings because I’ve got some fellows here!”

Leppington is a suburb brimming with potential and development, located 38 kilometres from Sydney’s CBD. The train station was the initial catalyst of change in 2015, allowing transport infrastructure and residential growth to follow—2021 ABS statistics announce nearly 10,000 people have moved in. To compare, when my father married my mother and left home in 1998, Leppington’s population was under 2000.

The drive to Ida Favretti’s residence is an impromptu tour guide of the suburb. Dad retells the excitement that came from trekking a 4km return journey in blistering heat to the tattered corner shop for an icy pole with his siblings during their youth, on the rare occasion my grandmother gave them pocket money. Nonno signals the new Coles nearby, but he’s more of a Woolworths guy.

There’s a heritage house set well back along Camden Valley Way my grandfather points out. The Raby Estate, granted to Alexander Riley in 1810, is a grand white mid-Victorian two-storey farmhouse high up on a hill in the neighbouring suburb of Catherine Field. Shrouded in eucalyptus with views to Sydney Harbour to one side and the Blue Mountains to the other on a clear day, a portion of the estate continues to be owned by the Mitchell family who bought it from the Rileys in 1833.

Leppington Public School is also a heritage site, established in 1923, and originally named after Raby. Its name changed as it contains bricks from the 1823 property of William Cordeaux, Leppington Park, which burned down in the 1940s. Leppington could have easily been called ‘Raby’, but instead Campbelltown LGA claimed the name for one of their suburbs.

A few minutes after 10, we navigate through ornate front gardens and a charming labyrinth of tiny roads, parking outside Ida’s cottage-like home in Cobbitty. The native plants decorating her lawn are prim and proper and the hydrangeas are in full bloom. There’s an assortment of garden gnomes and, oddly enough, miniature chickens around the entry. Dad and Nonno smile at them—there’s an inside joke somewhere here.

Ida doesn’t bother coming to the front door to greet us, rather squarks that “it’s open!” and that’s that. She’s shuffling about in a maroon tracksuit and slippers, cackling that she just had breakfast (like breakfast at nine in the morning was unheard of). When it’s my turn for customary embraces, Ida holds me firmly by the shoulders and looks at me with wild, cheeky eyes. It’s a sign that I’ve been welcomed into the fold. To my dad, she makes comments about my young age in a perfectly blended accent equally thick in its Australianisms and Italian dialect.

Her house is larger and more modern than you would expect for a retirement village. But her Italian roots show in the details; various crockery and religious memorabilia in a timber cabinet, a copper fireplace always turned on, rosemary plants tucked away in corners and a grand deck she personally asked for to host her large family.

Ida is strikingly bird-like. Loud and boisterous with a laugh that could rival kookaburras, Ida’s close-cropped silver hair might signify age, but there are memories and wisdom in the creases around her eyes. We small talk about King Charles III’s coronation as she brings out the tea. For an 88-year-old, it’s impressive how high functioning she is. Just as she sits down to commence the interview, the phone rings.

“The bloody phone!” she mumbles, which turns into a laugh. “Thank goodness I can talk. I’ve got all these grandkids. I’ve gotta be thankful that they keep an eye on me.”

Ida was born in Tuntable Creek, Lismore in 1935, a year after her mother arrived in Australia from Italy. Her father had arrived a decade earlier, from the same Italian region as my paternal family: Veneto, in the Province of Treviso, about half an hour’s drive from Venice. Her family moved around a lot; Ida rode horses to her primary school in Lismore, moved to Ballina for three years when she was nine, by 15 they were living at Harris Street, Sydney, until finally settling in Leppington in her late teens.

“By that time, I had left school and I just farmed with Dad because I was the oldest and we never had boys.” Ida slows her tapping on the tablecloth and shrugs nonchalantly. “So, I just become a boy.”

The chickens by the door make sense once Ida explains that the property her parents bought in Leppington was an established poultry farm. The move from city to pastoral was spurred by her father’s dislike of the Flemington market scene, and coming from an agricultural region in Northern Italy, the soil at Harris Street was impossible to grow on. She makes an outburst in her mother tongue that they weren’t able to grow radicchio, the bitter purple mother of all chicory to the Veneto people.

“You couldn’t even grow anything! If a war’d come, you’d starve!”

It was an agent who gave her father the poultry farm idea because he had three daughters. “The girls then can pack the eggs and pick the eggs up and then, you know, that’s a good idea,” Ida laughs.

The Leppington Ida first knew was vastly different to anything even my dad remembers. Thick, dense bush with spots of farms and paddock scattered throughout 15 square kilometres. All tracks were unsealed, besides the two-lane concrete Hume Highway, full of bumps and potholes, and the bitumen roads of Camden Valley Way, Heath Road and Ingleburn Road. The residents were mostly Yugoslavs, related families who had come before World War I, all growing tomatoes. Farms were predominately five acres, but the Favretti’s was ten, “an old house with about 3000 chooks on it already”.

Poultry farms are semi-intensive. The Favrettis began raising free-range chickens with their large yard, but it’s not a reliable method of producing eggs. Cages, Ida stresses, are cruel since the chickens wouldn’t survive for very long despite laying an egg every day.

“When they have a run-around, it was good for the chook. It wasn’t good for economics. So that’s why we got into vegetable growing.”

This change of gears coincided with the arrival of more Italian families moving to Leppington, including a “good catch”, the man who would become Ida’s husband.

“They [the Italian families] were all up in the bananas at Lismore,” Ida explains. My dad and grandfather nod in understanding—Nonna was in that troupe.

The Favrettis bunched vegetables like lettuce, spinach and beetroot.

“And those mongrel spring onions!” seethes Ida, slamming a gnarled fist to the table. She retells how my grandmother would always help her prepare the spring onions. “Gotta peel ‘em all. A lot of work.”

Zucchinis and squash were also pests to grow but for different reasons. Buyers want zucchinis without any blemishes, of a certain size, whereas the latter are small and prickly requiring protective gloves, long-sleeved shirts and a truckload of patience.

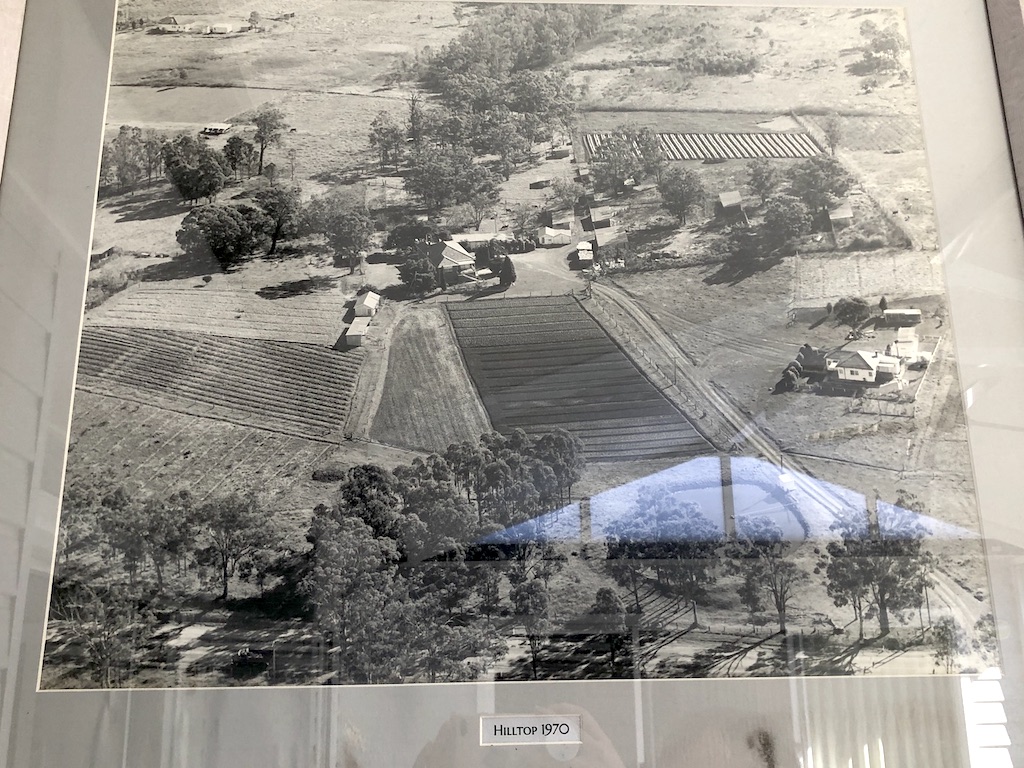

Nonno interrupts to comment that regardless, their farm was in “a good spot”. The area Ida used to live in is now being transformed into Leppington Heights. Dad fondly remembers their hill as Leppington’s “party central”. Later, I spy an A3 photograph of their property on the wall of her deck, dating from 1970. It deceptively disguises the amount of hard labour two houses and five vegetable fields requires into two-dimensions.

The piecemeal, uneven development that Leppington has endured, and will continue to experience until the Western Sydney Airport is finalised, is a familiar landscape in suburban Sydney. Much like how Parramatta Road is a patchwork of utility, commerce and neglect to the untrained eye, Leppington has places of charm for those who care to look at the details. Amidst the chaos of bringing the metropolitan to an area that has been semi-rural since 1821, are spots of faded glory.

Ida and Nonno reminisce about Leppington Progress Association Hall, built in 1956. The local place-to-be in its heyday is now a yellowing fibro building with dark green accents surrounded by paddocks off Ingleburn Road. The brittle ivory flyers stuck on the notice board look older than their 2018 to 2020 dates. Ida’s was the first wedding there since her father helped to build its foundations, but that isn’t her favourite memory of the hall.

Ida’s voice softens. She leans forward across the table, staring directly at me, eyes twinkling and grinning unabashedly. The two men in our company fade into the porcelain inside the glass cabinet along the wall.

“Once a month, there’d be a dance.”

It was the pinnacle of community spirit. Someone on piano, someone on the drums, a saxophonist joining in, creating a swinging symphony fit for festivities and neighbourly celebration. Italian, Yugoslav and Anglo-Saxon friends sharing barbeques and home-cooked meals. Young women dressed in their finest handmade gowns, the synchronised footsteps on the timber floorboards as the barn dance intensified. Grins sparkling up the hall as partners changed during the progressive.

My Nonno rather, enjoyed the monthly Prawn Nights, where the only thing on the menu was unsurprisingly, prawns. And boiled potatoes, kept in the jacket, cooked by the locals in the copper pans out the back.

“The Hall would be full chock-a-block of people!” Nonno Vic exclaims.

Ida’s strong love for community hasn’t wavered. In the middle of our conversation her neighbour Marie, a retired nun, walks in with a bunch of flowers. The jovial, friendly chatter animates the dining table—it’s a sign that a particular generation kept this specific type of community alive in Leppington until time caught up.

“You can’t stop progress!” Ida reiterates this throughout the interview. In fact, it’s this progress, sparked with Leppington Station’s construction, which resulted in a memorable day out. Ida, Nonno and a group of 13 of their friends caught the very first train from Leppington to Sydney, giggling in anticipation. Leppington Station is a patchwork of paradoxes at peak hour. New, but worn around the edges. Quietly grand, but humble in its position off Camden Valley Way. I imagine Ida’s squad to be the epitome of this chaotic, modest energy on the trip to town. The group relied on a tall friend to wave a red scarf around congested Circular Quay, to not lose half of them.

Ultimately, there’s no bitterness about the Leppington developments from Ida.

“It all depends on who’s there running the Council and the mentality of the people,” she said. “But I’m not sad about it. Not a bit.

“I’ve got to be thankful for the memories I had. I’ve never been as happy, and now all these new families get to make happy memories in Leppington too.”

As Dad and I drive home, we ignore the faint rail squeals in the distance and take in the scenic route through the unsealed roads and passing pastures. We talk about anything except the streetlights starting to crop up and when these tracks will turn into black bitumen.

But I recall Ida’s thoughtful taps on her dining table. “You can’t stop progress.”