In September 2022, Joshua “Josh” Gibbs opened Crosstalk Records in Leichhardt, some 14 years after the record store he worked at as a teenager was forced to shut its doors. His former store, Chatswood’s Ten Seconds Down, was one of the many victims of the rise of digital music and streaming services in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

“My first store that I worked at we shut in 2008 because sales had just dropped to almost zero,” he says. “I speak to a lot of people in the industry who are quite jaded, and I get it. A lot of people lost their jobs and a lot of people lost their stores.”

The digitisation of the music industry seemed to herald the end for physical sales. Amidst the current domination of streaming platforms, however, a boom in vinyl sales promises to resuscitate the obsolete medium.

Digital sales overtook physical in 2013 and have massively surpassed it since

Physical and digital music sales each year from 2011-2022 ($AUD) Source: Australian Recording Industry Association

The rise of digital music in the late 2000s and early 2010s signalled the demise of physical sales. For artists and musicians, the shifting industry has introduced new opportunities and posed new challenges.

Daniel Rojas, senior lecturer and program leader of the composition program at the Sydney Conservatorium University of Sydney, oversees its three undergraduate streams, BMus (Composition), Composition for Creative Industries and Digital Music and Media; and the Masters and Doctoral programs Bachelor of Music (Composition), (Composition for Creative Industries) and (Digital Music and Media).

“To me as an artist [the shift to digital] means leveraging our digital musical products as a vehicle for marketing and publicity,” he says. “Such leverage is geared toward audience building, obtaining performances, selling related merch, setting up a platform for donations, and gaining industry contracts.”

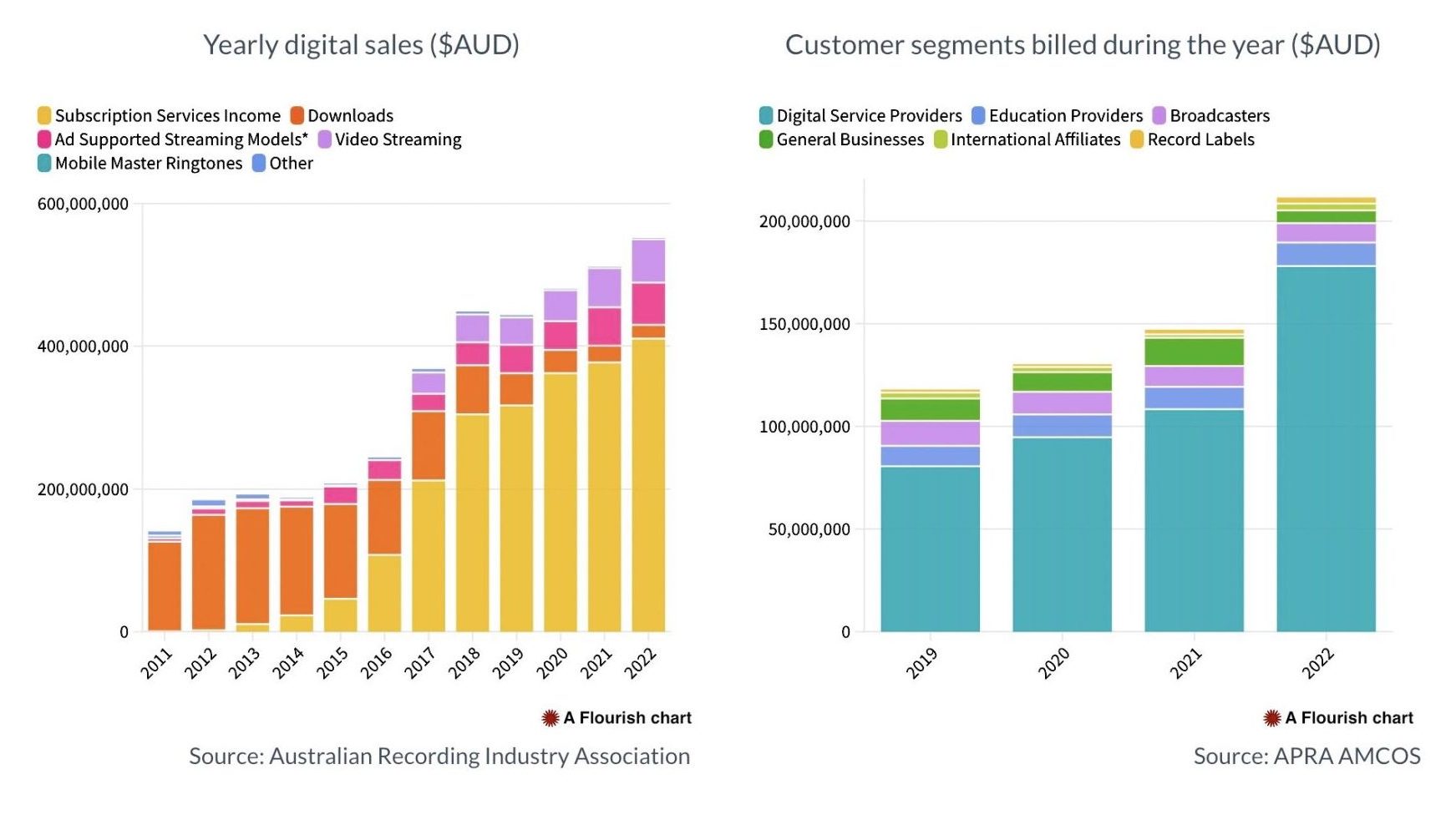

Subscription services and digital service providers dominate digital music sales

The recent massive increases in digital music sales can be mostly attributed to subscription services and digital service providers. Rojas says streaming services benefit artists by allowing “accessibility to a broader audience, ability for artists to connect more directly with audiences, and cheaper and greater immediacy for artists to release.”

However, streaming services are notorious for underpaying artists for their work.

“Using streaming services makes selling physical albums, where money can be made, more difficult, and low revenue collection lowers the perceived value of a production.”

Unfair pay is a major issue says record store owner Joshua Gibbs.

“Any artist, especially a local artist trying to make money knows that most money that you’re taking home in this day and age comes from physical sales, merchandise sales and touring,” he says.

“It’s the decommodification of some of this stuff that leads to new creative ways to get it out to people. This doesn’t mean a lot for musicians being able to get paid from their work. We’re still not at a good point in there, but then again Spotify’s not running at a profit so none of it is an incredibly sustainable solution.”

According to the 2020 ACMA Trends in viewing and listening behaviour survey, 61 per cent of Australians had streamed music on Spotify in the past seven days. This figure was more than double Spotify’s biggest Australian competitor, YouTube Music, which 29 per cent of Australians had used in the past seven days.

“The fact that Spotify has so much of the market share,” Gibbs says, “is based on the fact that they have the absolute best-looking product on the market. At least to me as a consumer, it’s the most functional. It’s the fastest, it’s the most conducive to discovering new music and it’s easy. Easy UI can’t be overstated in the digital age.

“I think a positive way forward is the fact that we’re seeing DSPs [digital service providers] like Tidal and Qobuz and a couple of others that have a smaller market share but higher payouts to artists.”

Another positive trend is the increasing pronounced pushes from Spotify and Apple Music users to up the amount they’re paying in royalties to labels and artists. Spotify has also added the option for artists to link tour merchandise and physical sales on their Spotify profiles, making them more easily accessible to fans.

While overall physical sales have plummeted, vinyl has steadily risen

Yearly physical sales ($AUD) Source: Australian Recording Industry Association

Gibbs says now is a really interesting time for physical music and traces that back to 2011-2012. “That’s when I started seeing people who were born after 2000 who had only grown up with free access to music basically, coming around to these things. It’s been beautiful watching it grow.

The rise in vinyl and physical formats as a response to streaming services is no longer out of necessity, he says.

“Time was vinyl was the best medium and pretty much the only medium you could buy music on for a long time.

“Humans have an innate need for physicality. They want to represent their taste, they always have. Whether it’s hanging art on our walls, having books out on our tables and in our bookcases, or having CDs or vinyl. And I think with streaming, the most interesting thing that happened was that people suddenly did discover that kind of urge to represent their taste in physicality. You would never walk into someone’s lounge room and say, ‘Hey, great Spotify library’.”

There’s also a certain kind of romance to vinyl, Gibbs adds, “just in the idea of dropping a needle and active listening”.

“Doesn’t mean you’re sitting there silently with your ears pricked up, trying to find little things in the music. But it’s just that one step harder than clicking on something and hearing it and then fast forwarding, and then hitting another album because you’re sick of the first two tracks of this album. Sitting down and dropping a needle is, for a lot of people, quite meditative.”

For Gibbs, vinyl’s resurgence has allowed him to open Crosstalk Records, “a record store slash hi-fi museum slash community space and arts hub”, in Leichhardt. After 21 years working in the music industry “from every which angle”, he says Crosstalk felt like a “logical end point” to his career so far.

And what does the future hold for physical music?

There were a “good few years” when people were able to argue that the vinyl boom was a bubble, he says.

“I definitely don’t think it is. Now that we have such a huge generation of people who have grown up around the idea of having access to everything but have turned around and embraced physical, I think that shows us we’re always going to have an element of that. They know they could stream it, and they probably have. But then, they want to attend a listening party and hold the record in their hand.

“And we’re talking about a generation of people that might not have two pennies to rub together, but when they do the first thing they do is save up to buy a record. And then they have it on their wall, because they don’t have a turntable. I get that constantly, but I think it’s fantastic.

“I think that’s really special. I can’t force myself to be jaded about something so lovely.”