The day after Australia voted No to an indigenous voice to parliament, Yes voters and Indigenous communities announced a “week of silence”.

A week later, they have found their voice.

Many are calling for renewed efforts to ‘close the gap’: to finally take action to deal with the high number of children dying before the age of 4, the high rate of teenagers jailed from the age of 10, and limited access to education, clean water and affordable fresh food.

After the devastating defeat, University of Sydney student and ‘Yes’ campaign volunteer, Yasmin Surman-Schmidt, urged legislative measures to regulate misinformation and lies.

She criticised the ‘No’ campaign for spreading misinformation and disinformation on social media, describing them as “absolutely tragic”.

Asked whether the failure of the referendum impacted her commitment to support First Nations people, she said it was “more of a wake-up call”.

“For me, it really reinvigorated my commitment to the cause,” Surman-Scmidt said.

“There were hundreds of thousands of [‘Yes’ campaign] volunteers. If all of those people are so supportive, surely that can come out of something.

“I’m here to support whatever indigenous people decide is the next step.”

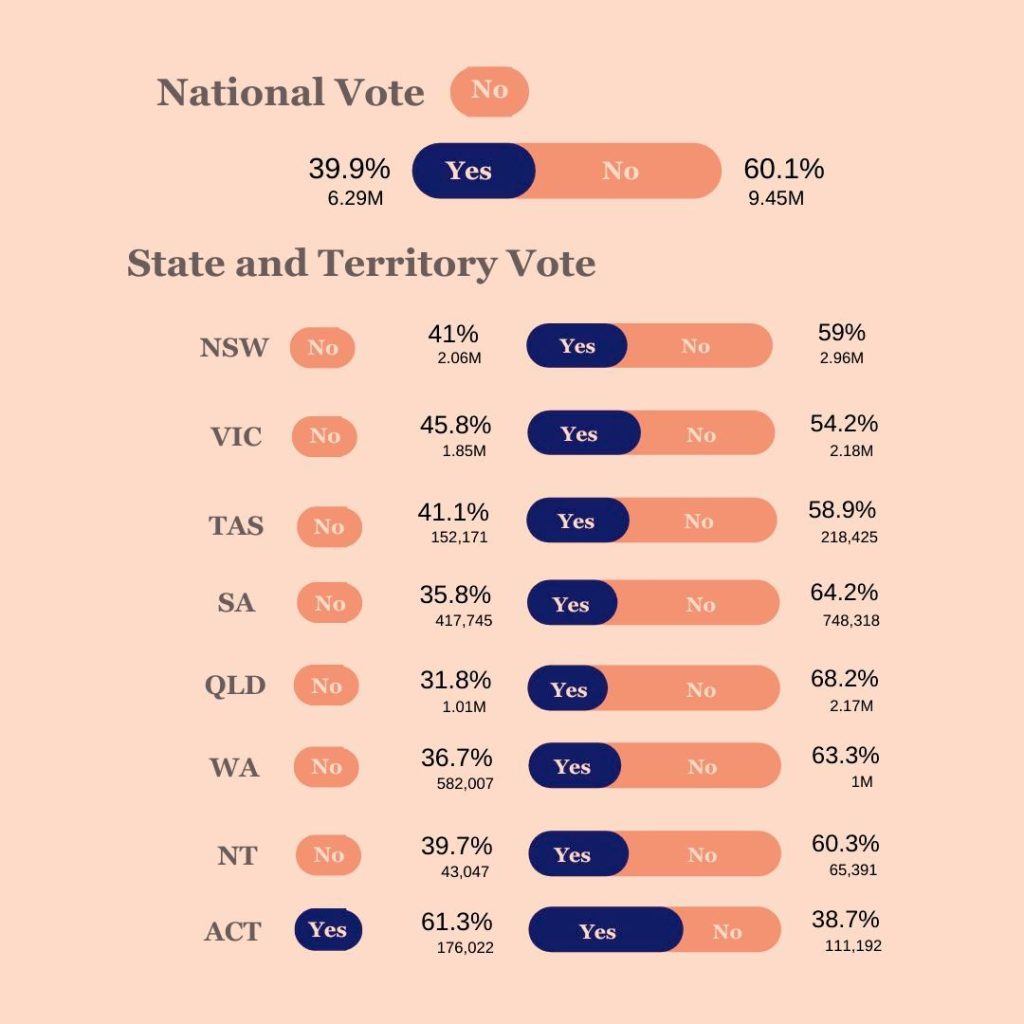

Originally from Canberra—the sole territory with a ‘Yes’ majority— Surman-Schmidt said she felt “out of touch with what the rest of the nation thinks”, alongside “disappointment” and “disbelief”.

“I think a lot of the ‘Yes’ people had this hope that the polling would be wrong and that Australians would really back First Nations people. But that proved not to be the case.”

Surman-Schmidt said learning “the violent truth” of Australia’s colonial history and the long-standing Indigenous disadvantages inspired her to support Indigenous rights. The belief that the referendum was First Nations people’s “fight for self-determination” led her to become a ‘Yes’ volunteer.

“Today indigenous people are behind in every health measure, behind in education, behind in employment, with higher incarceration rates. There’s obviously something wrong. I reckon if people opened their eyes, everyone would support it,” she said.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Performance Framework of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) revealed that from 2015-2019, the mortality rate of Indigenous children aged 0–4 was 2.1 times higher than that of non-Indigenous children.

It also revealed that in 2021, the incarceration rate of Indigenous adults was 14 times higher than non-Indigenous adults, with Indigenous children aged 10 -17 found to be 16 times more likely to be in youth justice supervision.

In the same year, only 68 percent of Indigenous Australians aged 20-24 had completed 12 years of education, compared to 91 per cent of their non-Indigenous counterparts.

As the nation continues to grapple with the implications of the referendum defeat, Indigenous groups and experts have called for action.

Vanessa Turnbull Roberts, a Bundjalung Widubul-Wiabul Indigenous lawyer and human rights activist, said on the ABC’s The Drum that the nation needs “a serious discussion” about racism and First Nations people’s rightful place in their homeland.

Goenpul Indigenous senior, Dale Ruska from North Stradbroke Island, said that recourse to “international legal options” were needed.

“I believe that we could only have any advantages to success as a people if we go to the International Court of Justice to have our First Nations sovereign rights recognised independently,” he told the ABC.

“And from that, hopefully, take our place at the Assembly of the United Nations and then use the international treaty models as the way forward.”

Catherine Liddle, chief executive of the Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC) also told the ABC that “truth-telling” was essential to get “needs-based funding” for Indigenous communities.

The referendum ‘No’ vote also presented challenges for the country’s politicians.

Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney addressed the referendum defeat on October 14, saying that despite the result being “tough” on Indigenous people, it was “not the end of reconciliation”.

“In the months ahead, I will have more to say about our government’s renewed commitment to closing the gap, because we all agree we need better outcomes for First Nations people,” she said.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese also said the country “must seek a new way forward”, and promised to “continue to listen and engage” with Indigenous Australians.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton brought a motion to the House of Representatives for a royal commission into alleged sexual abuse of Aboriginal children.

The motion failed receiving only 5 out of 32 votes, and drew widespread criticism.

Liberal backbencher Bridget Archer voted against her party, denouncing Dutton for “weaponising” child abuse for “some perceived political advantage”.

She also reprimanded her party for its ”inconsistencies”.

“We don’t want to divide the country by race [during the referendum], yet we are singling out abuse in Indigenous communities,” she said.

Indigenous Labor MP, Marion Scrymgour also condemned the proposal for “politicising” Aboriginal communities.

A joint statement that attracted 30 signatories of Indigenous agencies, child welfare advocates, and medical bodies, deemed the proposal “harmful” for isolating Aboriginal communities and perpetuating false, negative stereotypes of First Nations people. The group cited the most recent AIHW data, arguing that despite widespread child abuse in Australia, Indigenous children had a 2.2 per cent lower rate of substantiated child sexual abuse notifications compared to non-Indigenous children.

“These calls for a royal commission into the sexual abuse of Aboriginal children have been made without one shred of real evidence being presented,” the statement read. “They play into the basest negative perceptions of some people about Aboriginal people and communities.”

The ‘No’ campaign featured many Indigenous leaders including Warren Mundine and Michael Mansell who are expecting Treaty to become part of the discussion.

Senator Lidia Thorpe suggested consulting individual language groups to learn about their needs and desired solutions to better tackle Indigenous disadvantages.

But some ‘No’ campaigners called for a “close examination” of Indigenous communities. Damien Pace, a Young Liberal, questioned the need for more funding. Pace became a ‘No’ volunteer due to his conviction that the Voice would function as a “third chamber parliament” that would “undermine parliamentary democracy”.

“It’s not like we’re not doing things for Indigenous people; we’re doing a lot,” he said. “We want to know where the money is actually going and is it helping or not helping? If money is not helping, it’s not sound to keep asking for more.”

Pace also denied the need for “raising the status of Indigenous people”, calling it a “symbolic lift” that would not drive change.

He said he was “very pleased” with the referendum result.

Update:

A year after Australia voted No, only five of nineteen “Close the Gap” targets are on track. The Productivity Commission has since attributed the failure to ineffective models, lack of power-sharing, poor accountability, and misdirected funding to NGOs instead of Aboriginal-led organizations.

But Voice co-architect Tom Calma remains “hopeful”, recognising “meaningful population changes require many years”, he told the ABC News. He then called for increased needs-based funding and for a bipartisan government approach on Indigenous affairs. He still believes constitutional change is key to protecting Indigenous affairs from inconsistent policies caused by political shifts.

This year, the Albanese government introduced initiatives including $45 million for Indigenous scholarships, $79 million for justice reinvestment, and $777.4 million for the Remote Jobs and Economic Development Program.

State and territory governments are progressing on treaty efforts, with Queensland launching a truth-telling inquiry in July as part of its treaty process and Victoria to begin formal negotiations late 2024.