‘Being a deserter is better than being shot dead’: Kremlin’s ‘Real Man’ campaign fails

Russian men are rejecting the Kremlin’s latest hypermasculine campaign to recruit new troops to the Ukraine war.

Under the Russian President Vladimir Putin regime the word Muzhik, or ‘Real Man’, has become entrenched in popular culture. The latest Ministry of Defence advertising campaign is using this to appeal to the Russian men’s sense of manhood.

Key to this recruitment drive is a new online conscription model designed to crackdown on

draft dodgers.

Andrew Sokolov*, a 27-year-old Russian man, fled to China to avoid conscription.

“Being a deserter is bad, but it’s better than being shot dead or getting bombed,” he said.

Mr Sokolov is one of thousands who have rejected the Muzhik campaign and have fled Russia to avoid the new conscription bill.

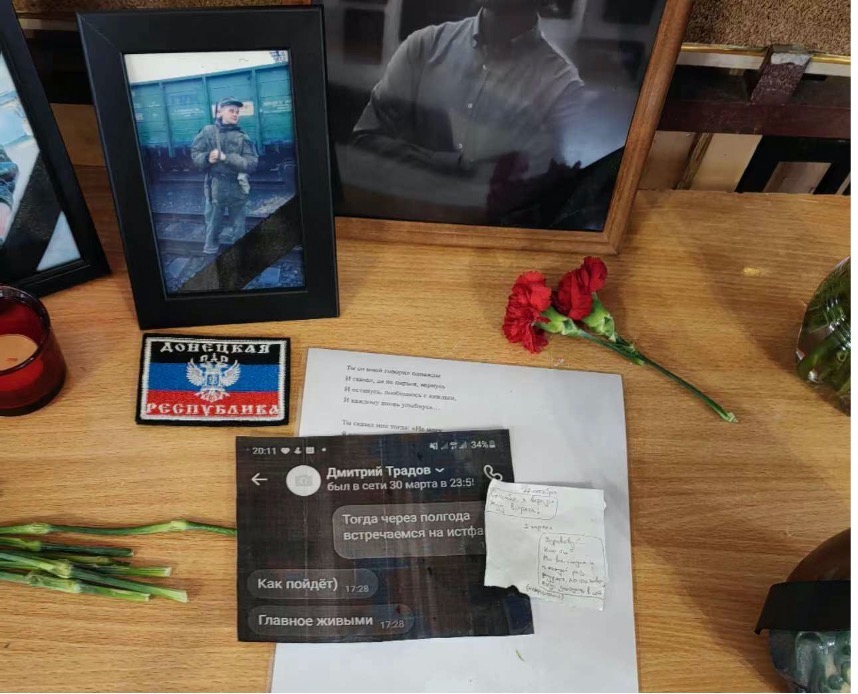

“Last year a student soldier died in the war,” he said. “He is only 21 and the university held a memorial for him. It really scared me, and I have been thinking about my future since.”

The Muzhik campaign is a powerful call to arms that even has a Hollywood angle with President Putin calling Leonardo DiCaprio a Muzhik after the star promised $1 million to save Russian tigers in 2010.

More powerful is the fear the new conscription campaign that calls up another 130,000 Russian men to join the Ukraine conflict has created. The new electronic draft system also closes loopholes that allowed people to flee rather than fight.

Up to 1 million young men have fled Russia since the start of what is now the largest armed conflict in Europe since World War II.

In July the Russian parliament passed the new conscription bill that raises the maximum age for conscription from 27 to 30. This widens the pool of men who can be sent to fight in Ukraine.

Mr Putin’s push to mobilise troops numbers through conscription has sparked widespread

protests.

Mr Sokolov said he was too scared to return to Russia.

“It’s not really stable in Russia now and I am afraid that If I go back, they will not let me

leave,” he said.

Masculinity and Patriotism

To bolster Russian troop numbers the Russian Defence Ministry has launched the Muzhik, ‘Real Man’ ad campaign that appeals to a sense of duty, manhood and nationalism.

The video features civilian characters like a security guard, fitness instructor and taxi driver, contrasting them with images of muscular soldiers in uniform, wearing helmets and carrying rifles.

One scene mocks a security guard standing near a stand of vegetables at the entrance to a

shop. This scene begins with an image of a soldier holding a military-style rifle guarding the

entrance to the shop, which is at odds with the mundane scene of people shopping for food

behind him.

The scene then shifts to an image of a security guard in the same position with the words:

“Did you dream of becoming this kind of defender?”

Other scenes ask a fitness instructor: “Is your strength really this? A taxi driver is asked: “Is this the path you wanted?”

The video ends with three soldiers emerging from smoke in uniform with Z patches, a

symbol for victory in Russia, and guns. The video then asks “You’re a Real Man (Muzhik). Be a Real Man” and the text on the video reads “serve by contract.”

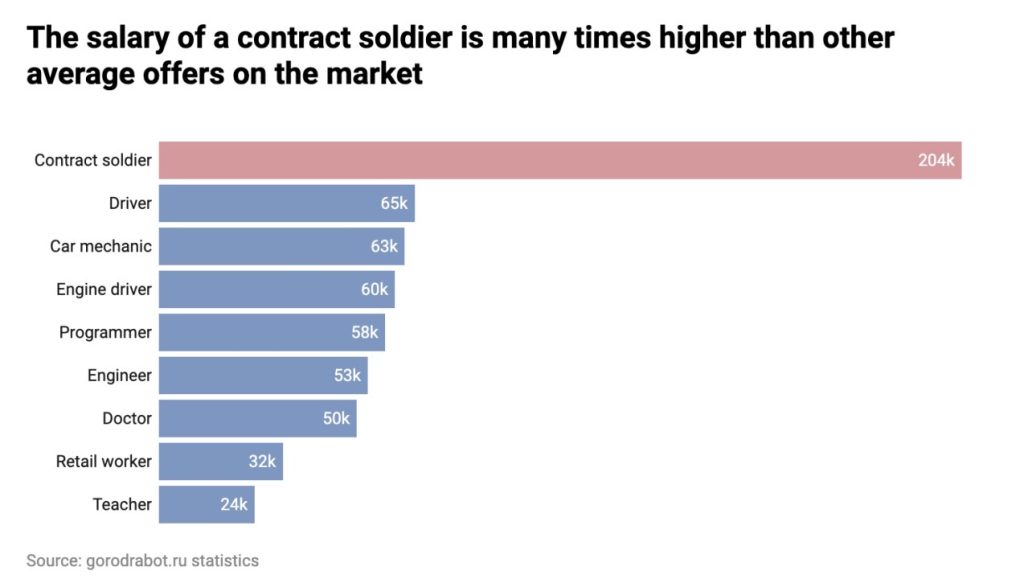

The campaign calls on men to sign up as contract soldiers and promises a salary of 204,000 rubles ($AU2,500), which is three times the average salary. It also plays with patriotism and presents active duty as a way to escape poverty and showcase heroism.

According to official statements, the starting salary for a Russian soldier fighting in Ukraine is 195,000 rubles (AU$ 3,156.74) per month, nearly 14 times higher than the average salary in some regions of Russia.

Mr Sokolov said the war was being sold as a way out of poverty for the 15 million people,

close to 10 per cent of Russia’s 143 million population, living below the poverty line.

“A lot of people in debt or in need of money will sign a contract to serve in Ukraine,” Mr

Sokolov said. “When they were hiring gunmen to join the Wagner Group [ЧВК Вагнер, a private Russian paramilitary unit of mercenaries fighting in Ukraine and elsewhere], they were promising really high salaries so people would join.”

In one of the series’ videos, a destitute grandfather is contemplating selling his cherished

car until his grandson intervenes and solves his predicament by enlisting in the war.

The Campaign

The social media campaign “I am Mobilized (Я мобилизован)” launched in VKontakte, the

most used social media software in Russia, also focuses on warrior masculinity.

The rhetoric of this emerging militarised Russian Government masculinity wave leans heavily on Soviet-era ideals. The message to young people remains consistent: they are called upon to fulfil their “patriotic duty,” and be regarded as “Real Men”.

Males from lower socioeconomic backgrounds feel the most pressure to enlist in

the military, viewing it as way to promote masculinity and establish social identity.

In her book Militarizing Men: Gender, Conscription, and War in Post-Soviet Russia, Dr Maya

Eichler underscores how military service has become increasingly associated with

masculinity. Stratified by social class, wealthier classes are spared from the horrors of war at the expense of the poor.

The human cost

The Russia Defence Ministry has maintained secrecy over the official casualty figures but

independent investigations shed some light on the Russian death toll.

UK intelligence estimates 600,000 Russians have died in Ukraine while BBC Russia has

released the names of more than 29,000 of the Russian fighters killed.

Regions with substantial minority populations, such as the Tuva Republic and the Buryat Republic, are bearing the bulk of war fatalities.

Buryatia, with 980,000 people, has lost 364 young men to war which is more than 25 times higher than Moscow, that has a population of 17 million people but has recorded less than 50 deaths.

Making the impact of this war even greater is the fact many Russians have close ties to the

neighbouring ex-Soviet nation of 44 million people.

The ties between the people of Russia and Ukraine were so strong that even as 150,000

Russian troops lined up along their border the majority of Ukrainians, 62.5 per cent, did not

believe the invasion would happen.

“Many Russians have relatives in Ukraine,” Mr Sokolov said. “The concept of war tears up many families [emotionally], and the war itself has broken many families.

“Can you imagine killing your relatives or friends?”

In Russia, an estimated 11 million people have relatives in Ukraine.

Traitors, Rebels and “Cyber Gulag”

The Russian government has implemented military-style censorship laws that tighten control over critics of the war. The laws dictate harsh penalties for ‘fake’ or ‘false’ information including jail time.

Moscow Municipal Council deputy mayor Aleksei Gorinov was the first to be sentenced

under the new laws. The lawyer received a seven-year jail term for “disseminating false information about Russia’s army” in July last year.

He faced charges after he criticised a council proposal to organise a children’s drawing

competition and dance festival while “children were dying” in Ukraine.

According to the human rights monitoring group OVD-Info 482, people have been charged

under these laws, with 136 sent to prison.

“You can be sent to prison if you openly support Ukraine or wear the Ukrainian colours on

the streets,” Mr Sokolov said.

In the first seven months of 2023, treason cases surged fourfold compared to 2022, with 82.cases reported from January to July 2023.

The increasing conservative censorship in Russia includes laws that ban expressions of

LGBTQ+ identity and gender transition.

Thomas Llyin*, 28, a member of the LGBTQ+ community from Saint Petersburg, said he not only feared conscription and being sent to Ukraine to “kill people”, but as a member of the LGBTQ+ community he is increasingly at risk of violence at home in Russia.

A Sphere Foundation 2022 survey found 83 per cent of LGBTQ+ participants had reported a growth in homophobia.

Despite the increasingly authoritative regime imposing strict laws against anti-government

rhetoric, Mr Ilyin admits to posting anti-war messages on social media and participating in

street protests..

He said that as a member of the LGBTQ community, he was concerned for his personal safety and has approached Swedish authorities seeking asylum.

Authorities have targeted both Russian and international social media platforms and what

Mr Putin has labelled “pure Satanism,” which encompasses western values and LGBTQ

rights.

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) characterises the escalating use of surveillance

technology in Russia as a manifestation of “digital authoritarianism”. This has been dubbed a “Cyber Gulag”, a reference to Soviet-era labour camps for political prisoners and the heavy reliance on technology in surveillance.

The Kremlin has isolated Russia’s internet infrastructure from the global web, creating its

own separate and tightly controlled digital environment. This isolation has made it easier to shape public opinion and stifle dissent,” Mr Sokolov said.

Russia has extended censorship laws to cover “defecting to the enemy” as treason, punishable by up to 20 years in prison.

RISING AUTHORITARIANISM IN RUSSIA TIMELINE

February 2022 – Russia launched the Ukraine invasion.

- March 2022 – The Russian government passed a bill that criminalises ‘fake’ reports regarding the war in Ukraine, and Facebook and Twitter were blocked in the country.

- March 2022 – March 2022 – Putin says Russia must undergo a ‘self-cleansing of society’ to purge ‘bastards and traitors’

- July 2022 – Russian authorities closed mass media outlets and blocked online content for disseminating ‘false’ news through new laws.

- September 2022 – The Russian government announced partial mobilisation, although some remote areas claimed it was a “100% mobilisation.”

- April 2023 – The Kremlin calls for ‘real men’ to prove themselves by joining the fight in

Ukraine. - July 2023 – There have been four times as many cases of treason initiated than in the entire year of 2022, with 82 cases reported.

- July 2023 – Russia raised the maximum conscription age to 30, it also launched digital call-up papers and a ban on prospective soldiers leaving the country.

Note: * Names have been changed to protect their safety.