CONTENT WARNING: This article contains mentions of sexual and gender-based violence, and spoilers for The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes.

Does life imitate art or fiction reflect reality? When considering dystopian novels and film, the answer lies on a pendulum.

The parent genre of speculative fiction intentionally illuminates a futuristic world birthed from our present society’s trajectory. These stories are foregrounded in truth but sometimes, to an extent, become prophetic.

And they’re popular too. Just recently, the film adaptation of the flagship young-adult dystopian series The Hunger Games’ prequel, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, broke $300M in the global box office. The franchise, led by Jennifer Lawrence’s Katniss Everdeen, is synonymous with strong female protagonists who have characterised the young-adult dystopian genre since.

The shift to elevating a teenage girl as the catalyst against tyranny was praised in the 2010s as a branch of fourth-wave feminism, holding powerful men accountable for their misconduct and the systems that enable such criminality to fester. When Katniss stepped on the scene, dystopias in popular memory represented women as invisible, pure reproductive objects, deprived of grace, beauty, intelligence or autonomy. They were nameless, confined to marginalised spaces, and brought into the foreground only when needed. Sound familiar?

Ballad, set a half-century before Katniss, follows 18-year-old Coriolanus Snow (Tom Blyth), the eventual president of the totalitarian regime controlling Panem that she dismantled.

The issue with these films is the trend for the plot to sympathise with the villains, rather than understand them. The intent is to depict complex characters, but with media literacy at concerningly low levels despite the content cycle we consume daily, awareness of the definitions of hero and villain, protagonist and antagonist, are blurred.

And when the film in question is a commentary on our current times, comprehension is critical.

Last month, the University of Sydney hosted the annual Australian Political Studies Association (APSA) Conference, where political science academics from around the country and overseas gather in a collegial atmosphere. Current research is presented and consulted in quiet lecture theatres and seminar rooms, or over morning tea, about international relations, climate change and popular culture.

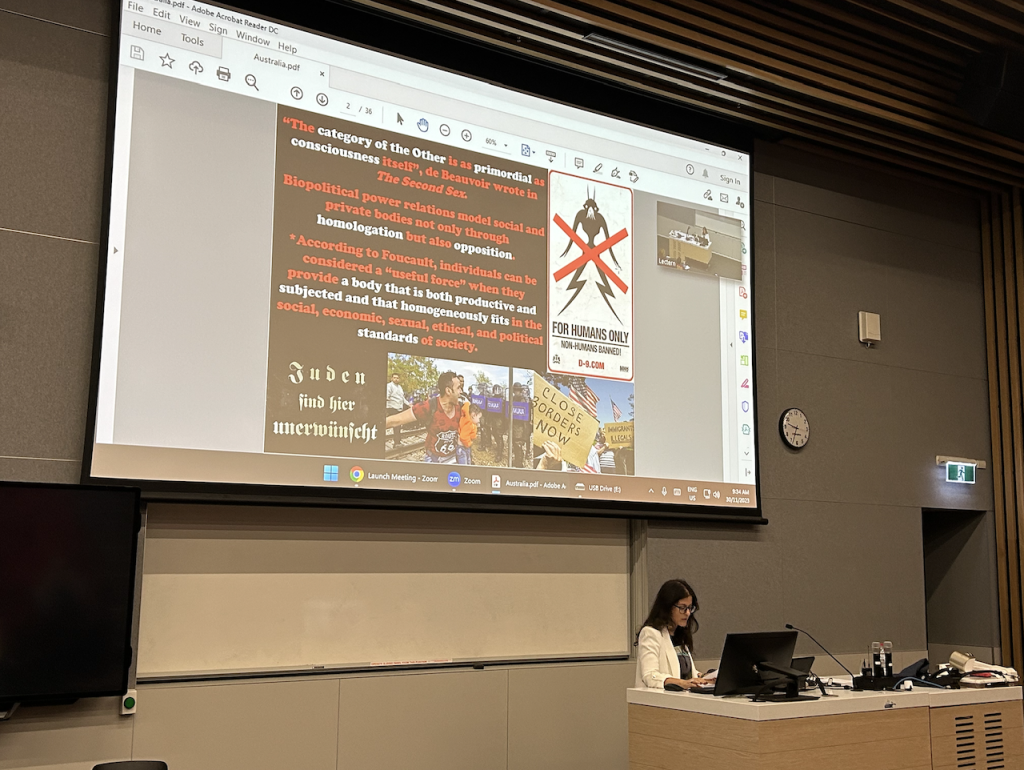

On a quiet Thursday morning, I sat in on a presentation by Dr Elisabetta di Minico from the Complutense University of Madrid of her research on ‘The Body of Otherness: How Feminist Dystopias Help Us Understand Gender-Based Violence’.

Secluded from the blaring heat outdoors in a disproportionately large lecture theatre for the few early risers, Dr di Minico’s words reverberated to the core of the feminist tradition. With an accompanying slideshow of news articles, she expressed ideas about how the dystopian genre’s allegorical tropes exaggerate violence, injustice and control of women to savagely depict the psychophysical entrapment we witness in the patriarchal real world.

Di Minico highlighted how language purposefully realises criticisms their accompanying feminist waves protested against, drawing on acclaimed novels: Swastika Night (1937) by Katharine Burdekin, presenting a future dominated by Nazism after Hitler’s victory over the Allies; Margaret Atwood’s classic The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), where patriarchal, white supremacist, totalitarian theocratic policies explicitly restrict the movement of women; and Australian author Charlotte Wood’s 2015 exploration of contemporary corporate misogyny and control in The Natural Way of Things.

“Stimulating in repressive environments, male sadism and hostility towards the female gender connect with fear, generating violence and a desire for destruction because destruction is the more reassuring form of possession,” suggests Dr di Minico.

“Dystopias help us to recognise gender-based violence is a structural phenomenon of our society and has a tremendous educational and critical potential because it promotes social-political response, participation and resistance.”

Listening, I could not shake the connections to The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes away. In Ballad, rather than a revitalisation of resilience in a world dominated by public state media control, the inescapable constructs and opulence of capitalism, extreme poverty, wars, genocides, and a doomed political climate for youths, we follow a young, entitled, arrogant straight white man claim his place of power and heighten the generational violence viewers are familiar with.

I sat down with Dr di Minico afterwards to discuss her research and opinions on why a dystopian franchise that sparked such a surge of female empowerment would give voice to the primary persecutor a decade later.

The first answer she suggests is the difference in mediums: “Film is a much more male-centric industry, as opposed to novels where women would have more agency.”

Consider the increasingly brutal examination of physical violence in The Handmaid’s Tale television series by Hulu compared to the novel through Offred’s eyes.

“It’s almost pornographic,” says Dr Elisabetta di Minico. “But it is the gaze that is corrupted.”

The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes is confronting from the standpoint that we encounter its female lead, the vivacious, kind, and enigmatic Lucy Grey Baird (Rachel Zegler), a singer from District 12 forced to participate in this year’s battle-royale to the death, through the perspective of Coriolanus Snow.

She is immediately positioned secondary to him. As Snow’s assigned Tribute in the 10th Hunger Games to mentor, his assumption of power is entwined with her survival. And as the two become romantically entangled, the analogy of control is curiously made clearer and simultaneously clouded.

Love is often another tool for dystopian authors to remind its characters and audience of humanity’s goodness, desire for connection, or as an extension of control. In The Handmaid’s Tale, affection is a “way to escape the nightmare” for Offred, says Dr di Minico.

In other classic dystopias such as Aldus Huxley’s (Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell’s 1984 (1949), Dr di Minico says love is a reason to create problems.

“It is the only way to reject this lack of individuality, this lack of empathy experienced.”

But classic dystopian literature leans towards a cynical, tragic ending for the protagonists. Women are subjected as handmaids or cattle, like they’re nothing, and there is an absence of genuine love. The subgenre of young-adult dystopia, however, targeted towards the youth, usually offers hope, and the promise and outcome of resistance.

“Young-adult needs to attract people and the easiest way to do it is by creating the perfect romantic triangle,” explains Dr Elisabetta di Minico. “We fight for love, so if we love someone, we are ready to destroy the world, to save them, to be with them.”

Ballad’s romance is more complicated, unlike the pure, genuine love between Katniss and Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson) in the original Hunger Games films that directed their motives and further exposed the two to the injustices of the Capitol.

Softened in the film, Coriolanus’ narration constantly refers to Lucy Grey as “his girl”. Note the abusive undertones. Snow’s political philosophy aligns with Enlightenment thinker Thomas Hobbes’s “Social Contract Theory” that an absolute sovereign power must assert dominance and subdue the people, who are naturally lawless and savage, to obtain peace.

Thus, the Hunger Games arena extends into the outer world, and Coriolanus’ so-called ‘love’ for Lucy Grey leads him to her home in District 12. To Coriolanus, love is having something you can call your own. All in the name of love, Coriolanus exercises control by lying, manipulating, snitching, threatening and attacking Lucy Grey and people she loves.

However, director Francis Lawrence uses a series of lovely montages and Tom Blyth’s attractive features to position the viewer in Coriolanus’ incorrigible eyes. We become part of the ignorant Capitol audience. It’s easy to be swept up into the enchantment and spectacle of it all.

Dr Elisabetta di Minico reminds me that romantic films often depict love in unhealthy ways, be it for drama or individual different definitions and expressions of the feeling.

“Some people experience love as possession. You cannot say this is not love. There are many kinds of love, and love is not necessarily something good.”

This incongruity, that love in young-adult dystopian films has become corrupted from its source of hope and female empowerment into a weapon of oppression, is a grim message for its young audience that perhaps Ballad exerts too subtly.

If, as Dr di Minico proposes, “the basis of political violence is a lack of empathy” then centering the film around a self-serving, narcissistic, calculative man like Coriolanus Snow, — who despite every opportunity to become a better person retains an unsympathetic mindset —Lawrence and the series’ author, Suzanne Collins, reinforce patriarchal oppression minorities face on and off screen onto the audience.

The tragedy of Lucy Grey Baird is that she is erased. Despite ultimately displaying the strength to protect herself, to achieve individual liberation, and foreshadowing that her songs and her voice can be found between the lines of Katniss’ revolution that leads to Snow’s demise, her name and story is forgotten to Panem and District 12.

Just as the countless women subjected to gender-based violence in our world are, and remain, without systematic change.

Suzanne Collins is on the record saying she will only write a story if she has something to say. Wars continue to rage across the globe, reproductive rights continue to be fought, and the need increases for more work to be done in Australia combatting the high rate of gender-based violence Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women experience.

We can only hope that in 2024, Collins’ warnings do not fall on deaf ears. A cautionary tale indeed.

If this article has caused issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call 1800RESPECT for 24/7 support. If in immediate danger, call 000.