Australian WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange has been granted the right to appeal extradition to the US following London’s High Court ruling heard on Monday.

Assange made his final appeal to avoid extradition in a two-day trial earlier this year. This week’s ruling came after the US failed to guarantee that Assange would experience a fair trial if extradited. As a non-US citizen, he would not be accorded the First Amendment right of free speech.

Dr Emma Shortis, Senior Researcher in the International Security Affairs Program at The Australian Institute, said the ruling had come as a relief for Assange and his legal team.

But she warned that it offered no guarantees for his freedom as it does not rule out the possibility of a future extradition.

“The punishment by process will continue,” she said. “Julian remains imprisoned and his health is still declining.”

Assange is facing 18 criminal offences surrounding the WikiLeaks publication of classified documents from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. These documents include evidence of war crimes committed by American troops.

The US accuses Assange of breaching the 1917 Espionage Act, a WWI law used to prosecute spies. In 2019, the US Department of Justice described Assange’s publication of the documents as “one of the largest compromises of classified information in the history of the United States”.

Assange is being held in London’s high security Belmarsh Prison, where he has been for more than five years. If Assange is eventually extradited to the US, he will likely face a prison sentence of up to 175 years.

But the stakes of this trial extend well beyond Assange’s own fate. Notably, he is the first publisher or journalist to be prosecuted under the Espionage Act.

Dr Shortis said the case has had an enormous tax on press freedom around the world.

“It sets a dangerous precedent that could give the United States the power to punish journalists simply for doing their job.”

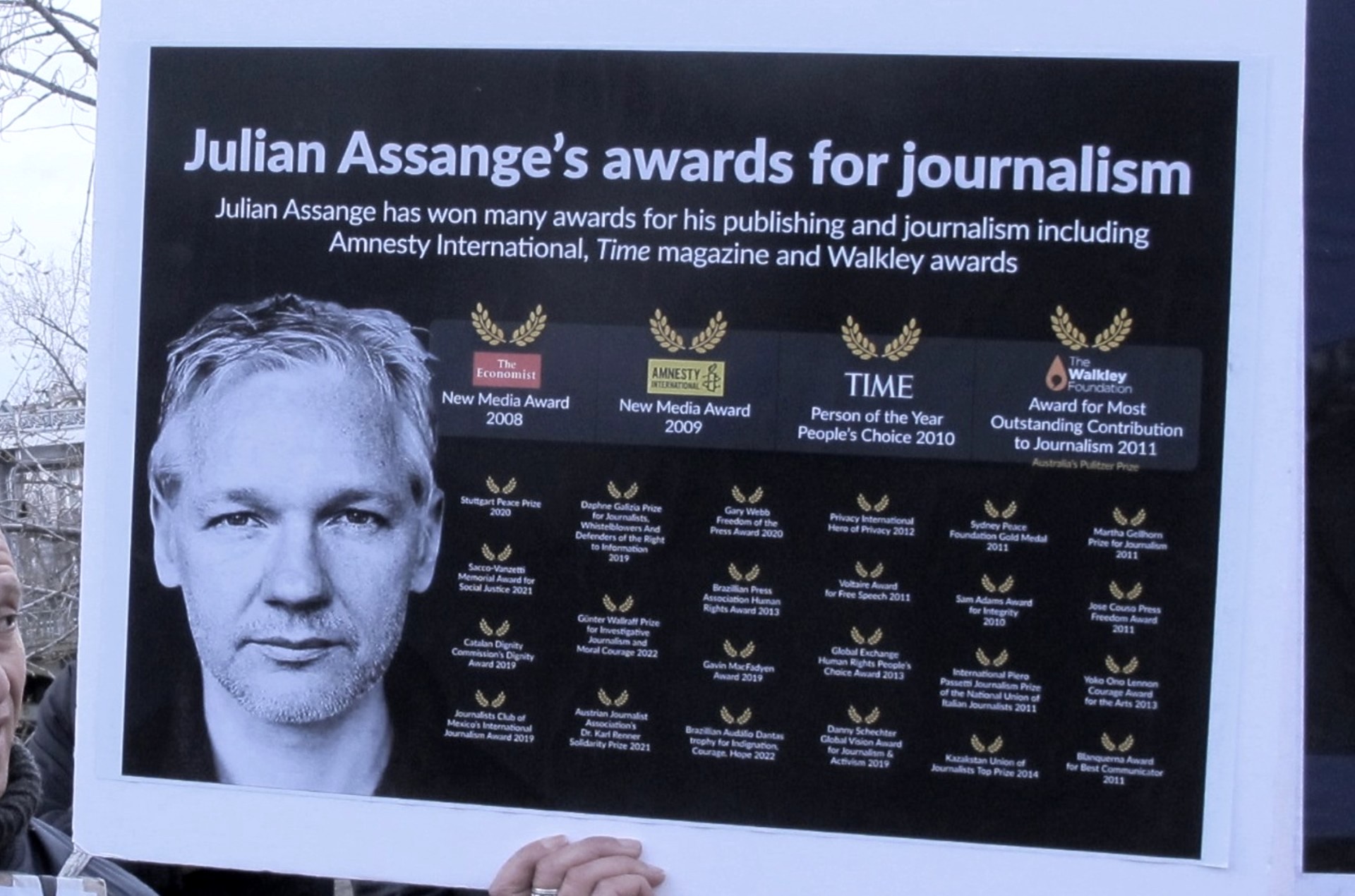

There has been debate around whether Assange can be considered a journalist due to his unorthodox publication practices. While the US argues that Assange was “going a very considerable way beyond the job of a journalist gathering information”, there are many journalists who disagree with this characterisation.

Carlotta McIntosh is an experienced Australian journalist who has been an active advocate for Assange since his initial arrest in 2012. She insists that Assange should be considered a “frank and fearless journalist”.

“Why shouldn’t Assange be considered a journalist? There are many forms of journalism these days. He was telling the truth. That’s all that matters.”

Assange founded the online publisher WikiLeaks in 2006. He published classified documents and other media that revealed violations of human rights. The website burst onto the media scene in 2010 when it leaked the video “Collateral Murder”. The 2007 video footage showed US soldiers firing at a group of civilians in Baghdad. The soldiers killed 18 people, including two Reuters journalists.

“WikiLeaks made such an extraordinary contribution to transparency and exposing the role of governments worldwide in suppression and secrecy,” Dr Shortis said.

At a time when many mainstream media outlets supported the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the release of this video shocked the world. It was a powerful reminder of what good journalism is meant to do: challenge those in power by sharing the truth. But in its decade-long pursuit of Assange, the United States has made it clear that good journalism will be punished.

Dr Shortis said a political resolution between the Biden Administration and the Australian government would be the fastest way to bring Assange home.

“The Australian government has the moral responsibility to demand that the charges are dropped”, she said.

In recent months, the Australian government has called for the US to drop charges against Assange. Ministers passed a motion in February that underlined “the importance of the UK and USA bringing the matter to a close so that Mr Assange can return home to his family in Australia”.

The US has largely ignored these requests, Dr Shortis said.

“I think the case exposes the imbalance of power in the relationship between Australia and the US,” she said. “Biden’s unwillingness to meaningfully engage with our democratic institutions is an appalling show of disrespect from a country we are told is our most important security ally.”

Until Julian Assange is allowed to return home, the future of press freedom hangs in the balance.

As Assange’s wife Stella told supporters outside the courts earlier this year: “Everything turns on the outcome of this case.”