Australia’s psychologist shortage leaves few treatment options for those experiencing depression.

Suffering? “Take a pill” can be a common response in Australia’s overstretched and underfunded medical system, says psychiatrist Paul Vroegop.

With mental health professionals in increasingly high demand – and short supply – therapy simply isn’t an option for many. But while antidepressants are life-changing for some, medical professionals warn that medication is no all-inclusive ticket to recovery.

Depression is the leading cause of disability across the globe according to the World Health Organisation.

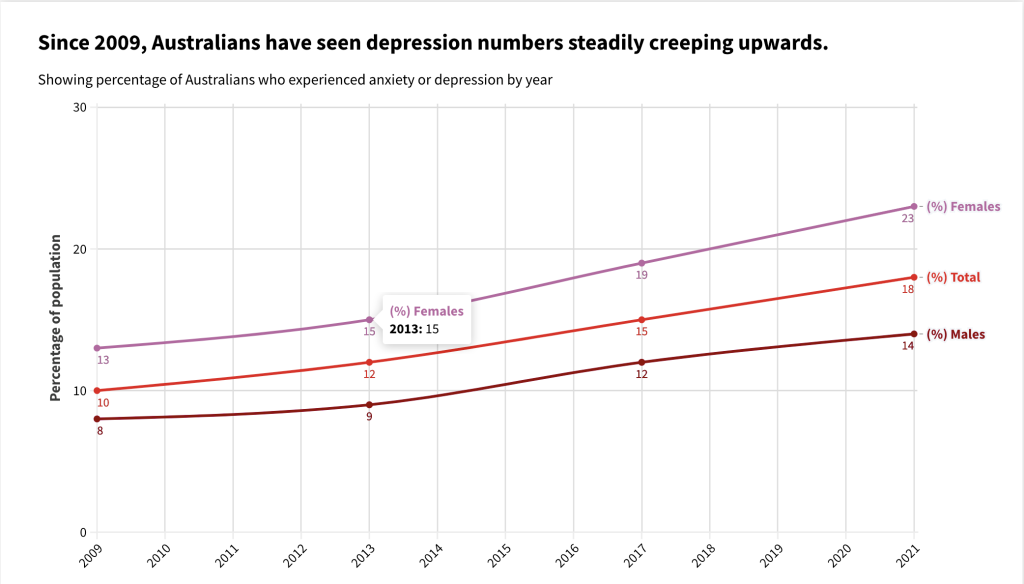

More men may be battling depression than the statistics show. The Black Dog Institute estimates that 72 per cent of men with mental health issues may be suffering in silence. Colloquially branded ‘snowflakes’, Millennials and Gen Z are often blamed for the increasing prevalence of depression.

Vroegop, who specialises in adolescent mental health, has a more forgiving rationale.

“I sometimes think that the rise in adolescent depression and anxiety is their rational response to what is a crazy and insane world,” he said.

Among those aged 12-24, antidepressant use has increased by 172 per cent since 2013. But this is a struggle widely shared. Antidepressant use in the 65 to 84 year-old population has grown at a similar rate to adolescents and in fact, by number, people aged 45-64 currently are most likely to be taking antidepressants.

The rise in dispensing antidepressants does not mean they have foolproof effectiveness. According to an Aroll study published in the Cochrane database, only one in seven people taking antidepressants will recover as a direct result of the medication.

Psychologist Ross Calear explains that experiences of depression are diverse. There is no treatment that is one size fits all.

“Antidepressants save lives and absolutely work for some people.”

It is the ongoing efforts of patient and prescriber to find one which is effective that seems to be a lucky dip.

Finding the right drug can be trial by fire with occasional quite unpleasant side effects like sexual dysfunction, anxiety or nausea. Calear explains that part of his role as a psychologist is to encourage the clients to persevere in working with their doctor.

Twenty one year old Mia Braagaard, who started taking medication for her depression in 2019, offers an optimistic outlook.

“I was in bed for six months before I started taking antidepressants,” she said. “Antidepressants enable me to live my life.”

Five years on she has a fulfilling social life and is working a stable job.

In separate interviews, both Vroegop and Calear emphasise the importance of a multi-stranded approach to mental health, with therapy paving the way to recovery.

“Antidepressants are no magic bullet. What they can do is get the ball rolling,” Vroegop said. “The real work is often behavioural and psychological.”

Before Mia started antidepressants, she found commonly cited self-help approaches patronising. “If I can’t get out of bed how am I meant to exercise?”

Antidepressants jump-started Mia’s motivation to get better — but therapy guided her recovery journey. For Mia, depression is an issue that doesn’t just disappear. Her psychologist helped her find techniques to live her life with it.

“I wouldn’t be where I am today without therapy.”

However, numbers of psychologists in Australia are not matching this unrelenting demand for help. And with APS reporting a whopping $300 price tag attached to most private sessions, therapy is out of the ballpark for many Australians.

Australian government research reveals that Australians living in rural areas face additional barriers in access, frequently waiting more than eight months for an appointment. In this landscape, general practitioners prescribe 88 per cent of antidepressants.

GP’s are under the pump to decide how to help a patient with appointments lasting only 10-15 minutes on average according to APA data.

“GP’s are often left on their own to make sense of a person’s symptoms, medication and individual differences,” Calear says.

Vroegop also expresses concern over the pharmaceutical industry narrative that a pill can solve all problems on its own.

“We have a shortage of psychologists and nowhere near enough psychiatrists.”