Australian-Balinese video artist Leyla Stevens presents her new work, PAHIT MANIS, Night Forest 2024, in the intimate setting of the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ Naala Badu building.

PAHIT MANIS is a meditation—one that inspires not only reflection on Bali’s future, but also on the culturally informed frameworks that can guide us in caring for and preserving our natural world. Co-curated with Artspace, this exhibition is part of the Art Gallery’s Contemporary Projects series, which, highlights the work of artists from NSW.

The dark space envelops the audience in a moving and breathing video piece as it moves between animated sequences, documentary style footage, and a powerful performance by a Dalang (Indonesian puppeteer) in training.

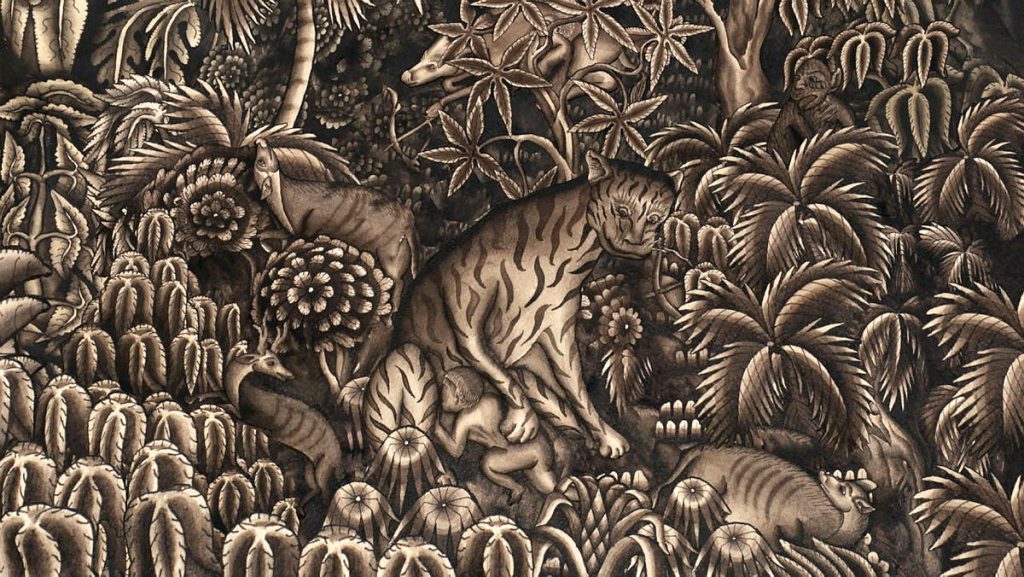

The film toys with ideas of the fluidity of culture. It becomes a collaborative piece between artisans working in ink within the last colonial period in Bali, starting the conversation of holistic and spiritual connections and rituals to conserve and connect with nature.

As a starting point the drawings break through lenses of anthropological study, recentering narratives of the spiritual teachings as mentioned in the Tantri Tales depicted.

Stevens’ work aims to overwrite these Western systems of knowledge, under which the drawings were originally created, to rethink how audiences can engage with the histories and moments represented outside the logic that continually framed them.

Stevens’ role as an artist is constantly shifting, moving between creator and educator, and in PAHIT MANIS, the film becomes something greater than its medium. The animated sequences—vibrant waves of ink and intense imagery of man’s struggle—seamlessly transition into the performance of the Dalang, whose voice carries a poignant, almost melancholic tone over soundscapes of forests and groves. It is a collaboration born from a deep, evolving understanding of traditional practices, yet always rooted in the present and connected to the people and spaces that define it.

In chatting about PAHIT MANIS, both Stevens and Artspace curator Johanna Bear reveal deep personal insights into the material and conceptual output of this larger research project.

Question: You mention this connection between the ink drawings as symbols of anthropology and colonial understandings of Bali, as well as a tool to reveal hidden histories behind these foreign ideas. Can you expand on this connection?

Lelya Stevens: “There’s so much scholarship around Bali, and this huge kind of field around Bali from the arts and literature, and from the anthropological and cultural. But often when we speak about these forms of knowledge, they have been produced through Western systems of knowledge.

“These sorts of histories and artefacts and artworks were produced during Bali’s colonial era, and the ways they became part of collections in Europe or in America have always been seen through a Western framework. A lot of my work has been an attempt to rethink how to engage with those stories; those histories and moments being represented in paintings outside the logic that have continually framed them.”

Question: Do you think your work, Pahit Manis, achieves that?

Lelya Stevens: “There are those ideas that Balinese culture is somehow divorced from global politics. You have these iconic images, like gamelan and dance and the rice fields, and all these things that appear very exotic. And somehow it’s talked about in a very ahistorical and temporal way.

“So I think a lot of what my work is doing is showing that so-called traditional cultures or ancestral practices are very much embedded within. Of course they’re political, of course they’re economical, of course they’re embedded in all these other different systems.”

Johanna Bear: “I think that for a lot of people in Australia there is this particular idea of what Bali is. And Leyla’s work for many people would be an encounter with a Bali that they’re less familiar with or less aware of.

“It’s very much from a local perspective rather than this foreign gaze, of people coming into Bali for holidays, for leisure, for partying. It’s a big thing that a lot of Australians would travel there for. And Leyla’s films would offer a different kind of insight into the incredible philosophies, these connections to the natural world, the spirit world and artistic practices that are also found in Bali.”

Question: I see the political side in the way you also discuss conservation and ecology through these traditional practices and philosophies. You also use these histories to explore more contemporary problems.

Lelya Stevens: “For many years Bali has been going through a major environmental crisis, facing issues of mass waste, water pollution and deforestation. But when you look toward traditional philosophies in Bali, you find there is already a blueprint of how you can look after and prioritise the environment in a much more holistic way.”

Question: Some of the dialogue didn’t have subtitles. Is that for a reason?

Lelya Stevens: “The subtitles do end up appearing, but I wanted [them] to not interfere too much. I’ve timed the subtitles to just quickly show the meaning of what she’s saying sometimes towards the end. She [the Delang] might say a sentence that actually stretches out through singing a couple of minutes, you know?

“I actually hate putting subtitles in. I often think because I work with performance-based collaborators sometimes the emotion of the performance of what they’re doing does translate. In this case, it was important. There were small decisions, like maybe not to translate immediately but just let the audience hear it first.

“And then you briefly just put the translation up. Little things like that I hope allow the audience to just be present with what’s happening on the screen a bit more.”

Question: With the emotions taking centre stage, I definitely felt it with the close-up of the puppeteer’s face and that prolonged sort of silence. She’s looking at you, you’re looking at her. Do you think there is an aspect of personal storytelling rather than this sort of umbrella-like Bali cultural history?

Lelya Stevens: “The project shines a light on the collaborators that I work with. She’s embodying a character, so her role is a little bit different. And the art form of being a Dalang, the shadow puppet master, is that you cann channel all these different characters, all these different voices. So it requires someone to actually be quite powerful in themselves.”

Johanna Bear: “From my perspective, I would say that’s something she’s having to navigate in a way that is this subtle personal interest, in often introducing or not introducing but shifting focus to narratives of women.

“There are more personal histories threaded throughout the work as well. And you know, you list all the names of those painters at the end of your film. We put that on the wall in the exhibition space.

“There’s this element of the personal that’s sort of an undertone. There are people at the core of this, and focusing attention on those individuals and their works has been very much a part of this project.”

Question: I really like this whole idea of diasporic practices. What is your positioning on the question of reclamation, of keeping these histories stagnant or into the future?

Question: I really like this whole idea of diasporic practices. What is your positioning on the question of reclamation, of keeping these histories stagnant or into the future?

Lelya Stevens: “Bali’s actually quite unique in the sense that it’s got such an alive culture. So these are so-called traditional practices that are happening now in Bali; whether it’s cross painting or dance or song, they’re alive. They’re continuing today, yet there’s an evolution of it. All those practices sort of absorb what’s going on around them; these sort of contemporary things that happen. It’s very flexible. What’s important is that the form can be fluid, that the same meaning can be transferred.”

Question: What advice do you have for emerging creatives and researchers?

Lelya Stevens: “Just learn from each project. Doesn’t have to be the best, most amazing thing. Every time you know your project, your practice continues.It’s part of a continuum. So I would say use each project as a way to learn and deepen your own ways of being an artist.”

PAHIT MANIS, Night Forest is on display at the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ Naala Badu building, lower level 2 until February 16, 2025.